Description

Almost as soon as work started to build the canal, artists and writers were recording the grand scale of the engineering projects.

From Gledrid, where the canal now becomes a World Heritage Site, the landscape changes from the flat and open plain of south Cheshire and north Shropshire to the hills and valleys around the rivers Ceiriog and Dee. These were already popular places for visitors and the construction of the great monuments of the canal were generally welcomed as enhancing, rather than spoiling the views.

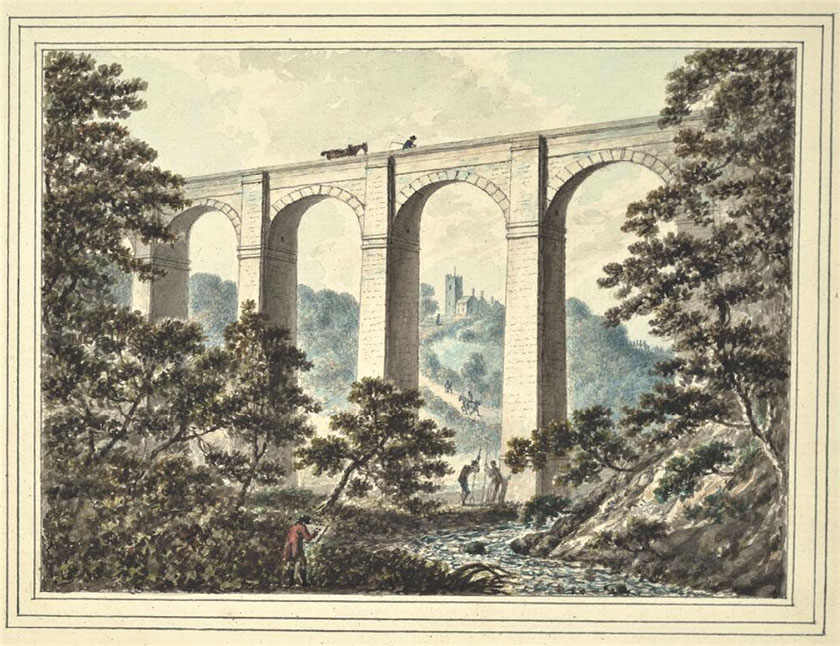

Both professional and amateur artists made detailed drawings of the sites, especially the aqueducts at Chirk and Pontcysyllte. Sometimes they made personal sketches for themselves, sometimes they were illustrating the writing of other observers. Some artists produced full oil paintings of the structures as the fame of the constructions spread. Others included them in the wider landscapes they painted, where the aqueducts were considered as just part of the view.

Paintings, drawings and engravings of the aqueducts can tell us a lot about how people thought of the world around them. The aqueducts were not just objects in their own right but symbols of human achievement, in harmony with nature but taming it too.

Street Art

Canal and River Trust have been running street art events to brighten up some of the urban areas that their waterways run through. The canals continue to inspire new artists and new styles after nearly 250 years. Click here to see the video.

More Information About Paintings

The landscape of north Wales attracted artists for its romantic beauty. Richard Wilson (1714–1782) painted this view in 1769, looking west from Wynnstay near Chirk, into the Vale of Llangollen. Twenty-five years later, Pontcysyllte Aqueduct would cross the centre of this scene. Smoke from limekilns at Froncysyllte show where the canal would be built.

In 1799, Richard Colt-Hoare saw Chirk Aqueduct under construction. He wrote that “its present unfinished state renders it perhaps more picturesque to the painter’s eye.” He made sketches of the site, as did J.M.W. Turner. Others sketched Pontcysyllte Aqueduct, including Rev. John Breedon, who clearly shows the wooden platforms the builders worked on.

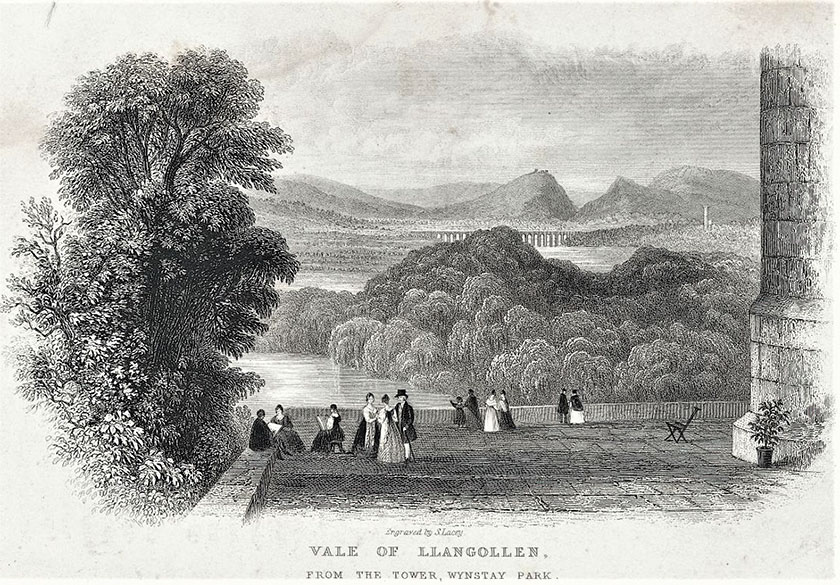

Nant y Belan tower was built in 1800, for views of the Wynnstay estate and the Dee valley while Pontcysyllte Aqueduct was also being constructed. Images of the Williams-Wynn family and guests on the terrace view show how the aqueduct had quickly become accepted as a part of the picturesque landscape.

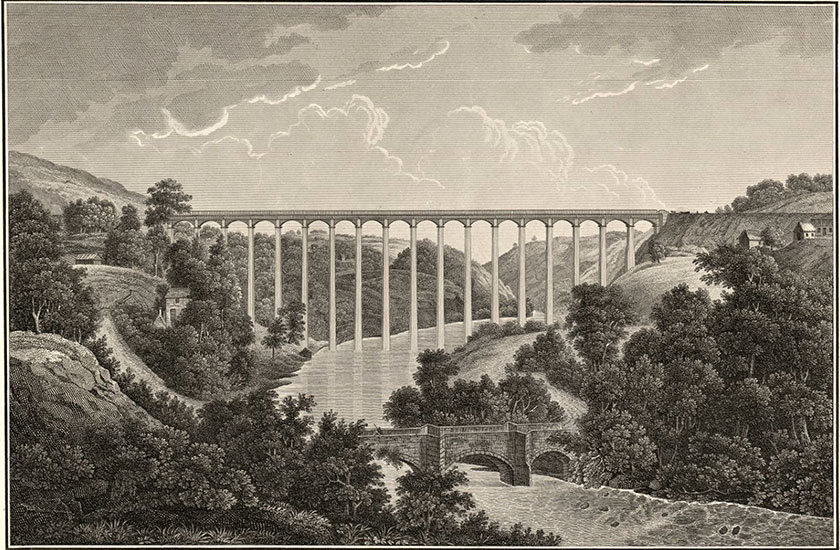

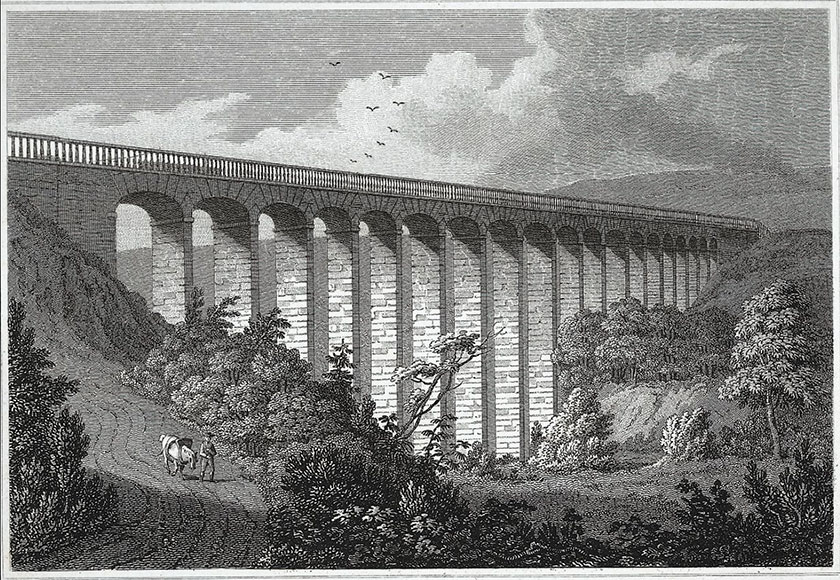

In the most common view, looking east, Pontcysyllte Aqueduct is tall, slender and precise. The old bridge is low, heavily built and irregular. The bridge is in the foreground but always overshadowed by its newer neighbour. Pictures, such as this 1821 French edition, use the comparison to enhance the qualities of the aqueduct.

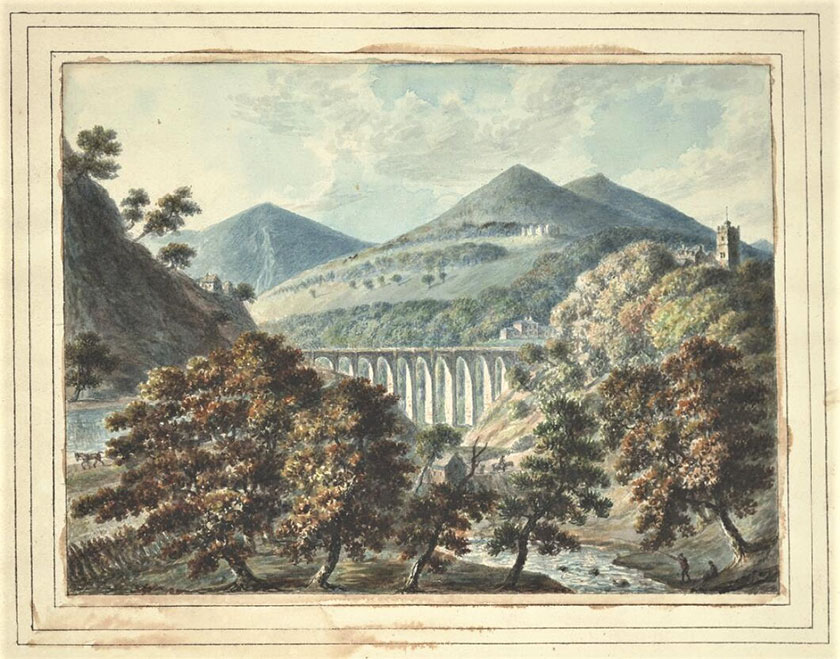

The canal was not the first great construction in the landscape. Views looking west often show the castles of Dinas Brân or Chirk on the hills behind the aqueducts. John Ingleby’s painting of Chirk Aqueduct exaggerates the size of the hills to emphasise the difficulties the builders of the structures had to overcome.

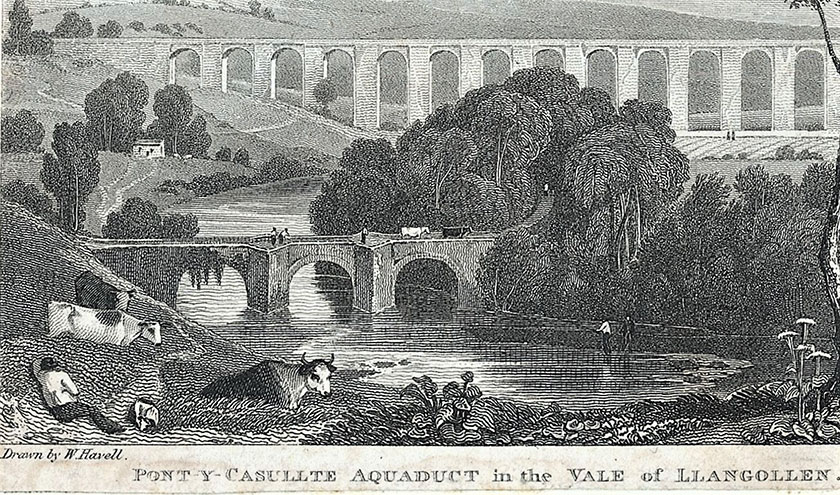

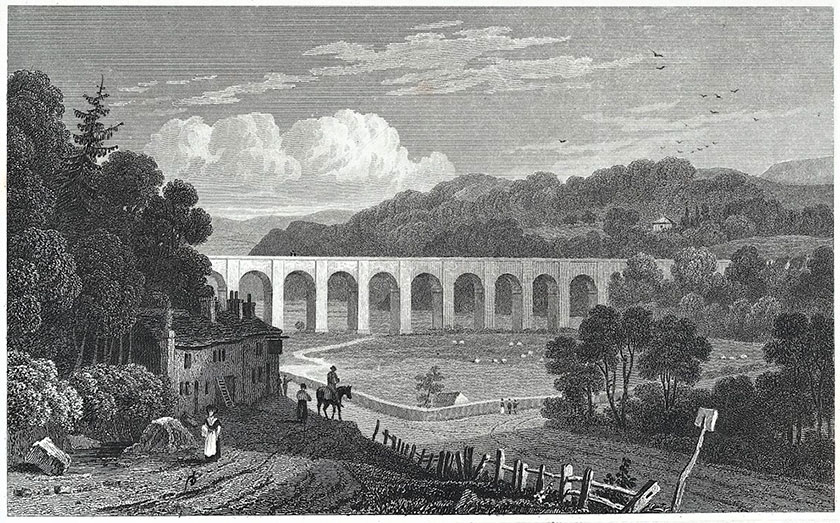

Many early observers commented on how well the canal fitted into the countryside, something still enjoyed by visitors today. Artists showed this by including stereotypical rural images alongside their depictions. Animals, people resting in fields and men fishing in the river were frequently included and are all in this engraving by William Havell.

Artists often included a portrait of themselves or another artist within pictures of landscapes. This wasn’t just flattering themselves. It was a visual hint to the viewer that the scene they were looking at was worthy of artistic attention. The artist in John Ingleby’s view of Chirk Aqueduct is almost hidden in the trees.

When Thomas Telford was elected as the first president of the Institution of Civil Engineers in 1820, Samuel Lane painted his portrait. Telford posed for the painting in a studio but Lane included a view of Pontcysyllte Aqueduct through the window. Did the artist or Telford himself choose this as his greatest monument?

The fame of Pontcysyllte Aqueduct spread rapidly after it was opened. Before photography was widely available, printed engravings were produced to illustrate newspapers and magazines. They were also sold as souvenirs. Henry Gastineau painted a great number of sights around Wales to be reproduced as popular prints, including both Pontcysyllte and Chirk aqueducts.

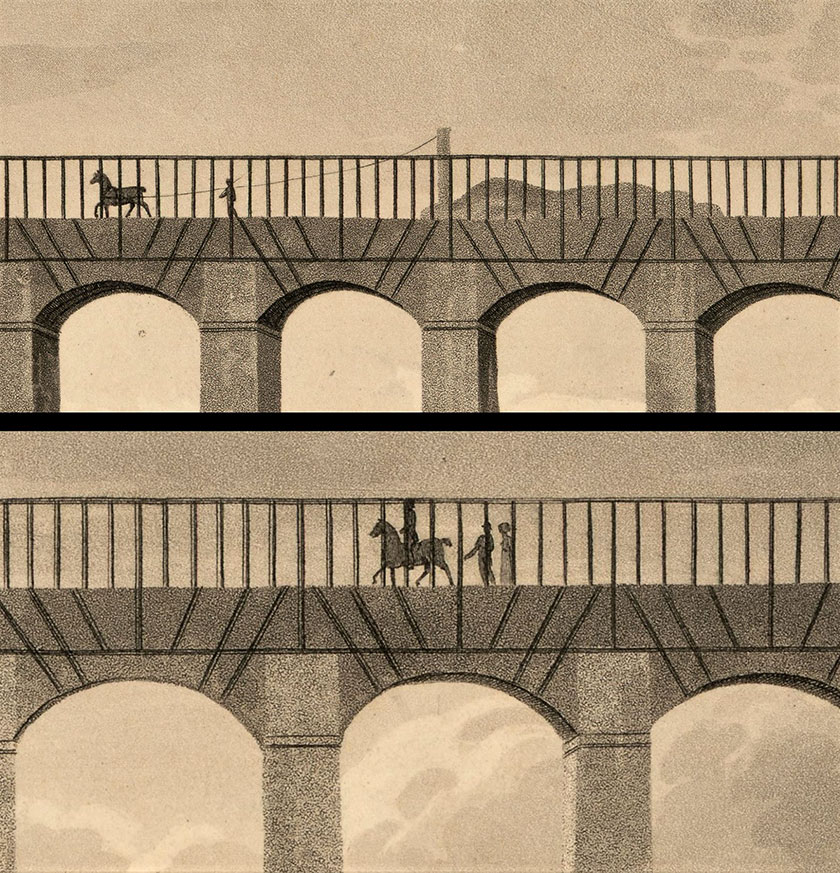

An engraving is produced by copying an original picture onto a printing plate. Sometimes the engraver would copy another engraving and over time, mistakes would start to appear on the pictures. In this 1828 image, the trough above the arches has disappeared and the railing is on the wrong side.

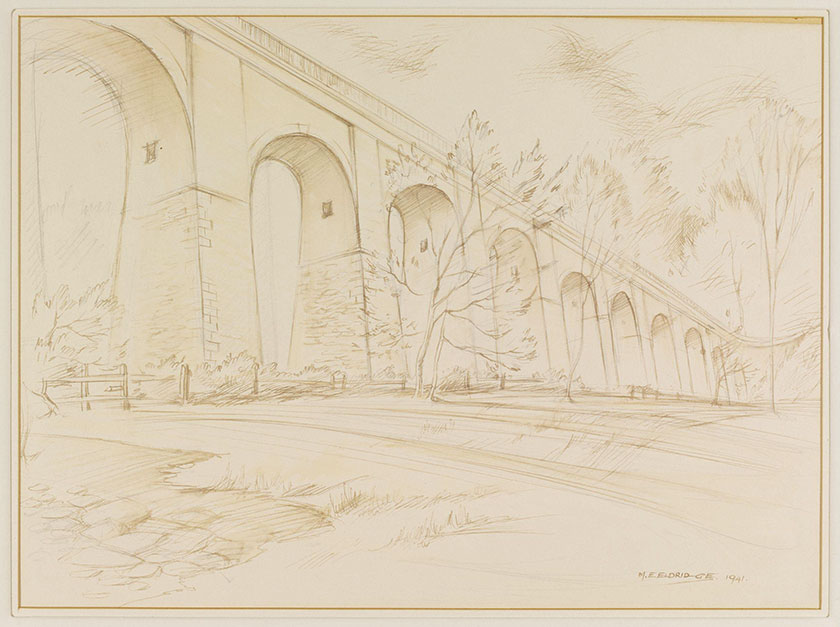

Chirk Aqueduct was the tallest in Britain when it was built, only to be beaten a few years later by Pontcysyllte. To emphasise the great heights, artists would paint them from very close to the base, looking up into the arches. This 1941 watercolour by Mildred Eldridge shows Chirk Aqueduct’s solid weight on the ground.

Sometimes it is best not to look too closely at a picture. What can look good in the overall composition might not stand up to close attention. The horses and people in this 1806 engraving by John Parry are beautifully detailed. Unfortunately, they are much too small when compared to the aqueduct railing.

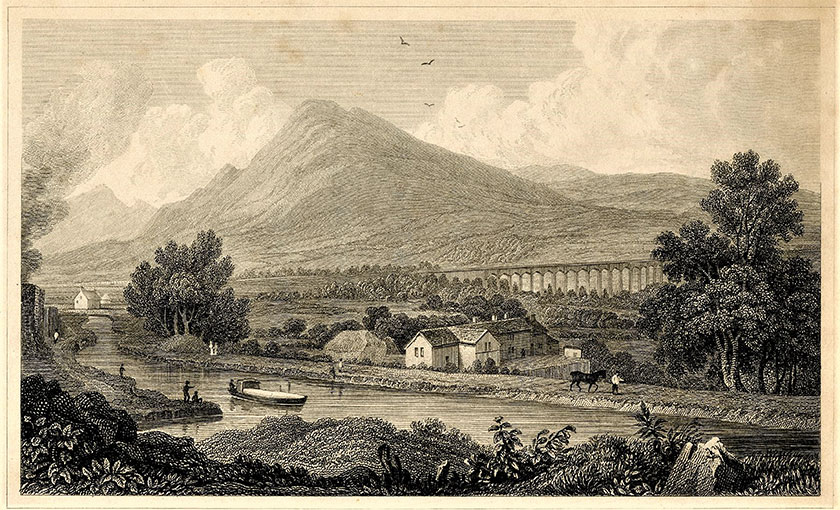

Much of the landscape would have been filled with industries but these are almost never shown in paintings of the canal. The smoke from the limekilns at Froncysyllte can often be seen however, perhaps demonstrating how strong it was. In this 1836 image by Henry Gastineau, you can see the kilns on the left.

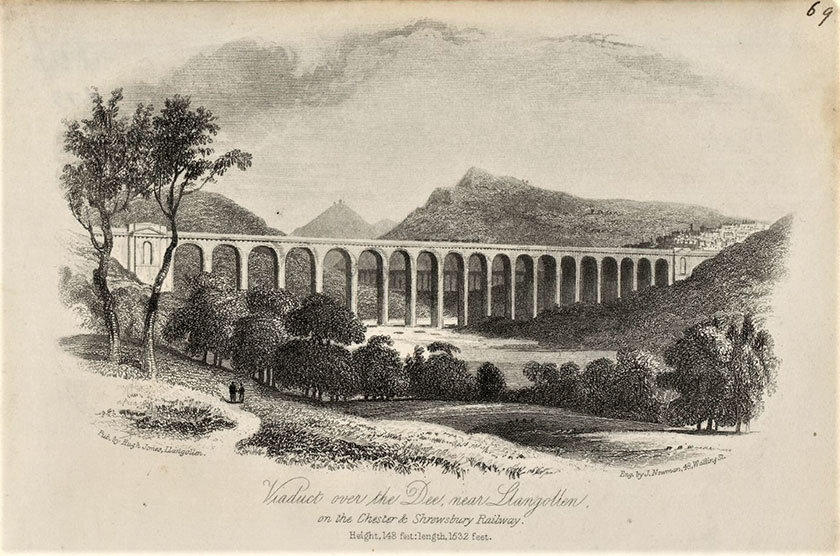

In 1848 the railway viaducts at Chirk and across the Dee opened. With faster, cheaper services, public excitement turned to trains and away from the canal. In art too, the aqueducts started to literally fade into the background. In this engraving of the Dee Viaduct, Pontcysyllte Aqueduct is just a distant shadow.

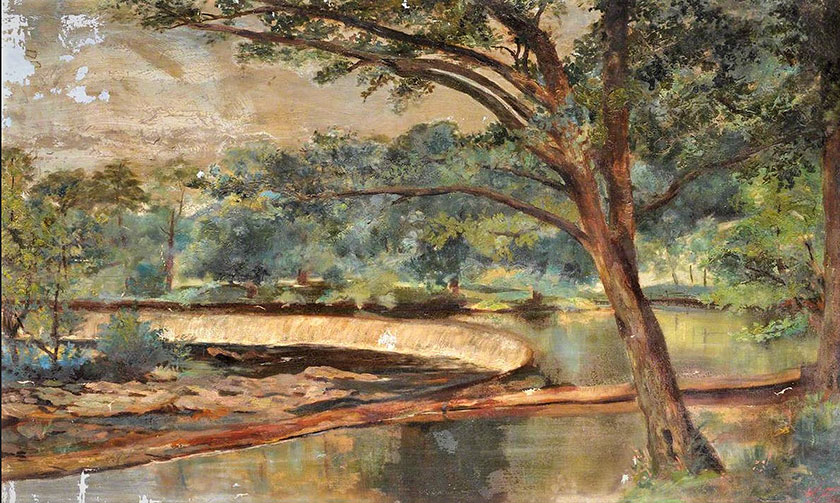

The aqueducts were not the only parts of the canal to attract artists. Horseshoe Falls had been a popular spot for visitors and landscape painters even before the canal and weir had been built, and they continued to be so. W.K.Fuge completed this oil painting in 1894.

Photography was invented in the 1830s but it was not until the 1860s that souvenir pictures of landscapes and attractions by professional photographers became widely available. This 1860s image of Pontcysyllte Aqueduct by Francis Bedford of Chester is among the earliest known. The composition with the bridge still follows that of earlier paintings.

The lack of light made Chirk tunnel of less interest to painters than the aqueduct. Photography changed that and views into and out of the tunnel became possible. Geoff Charles’s 1958 image captures the melancholy stillness of the canal after the working boats had disappeared and before the pleasure boats arrived in numbers.

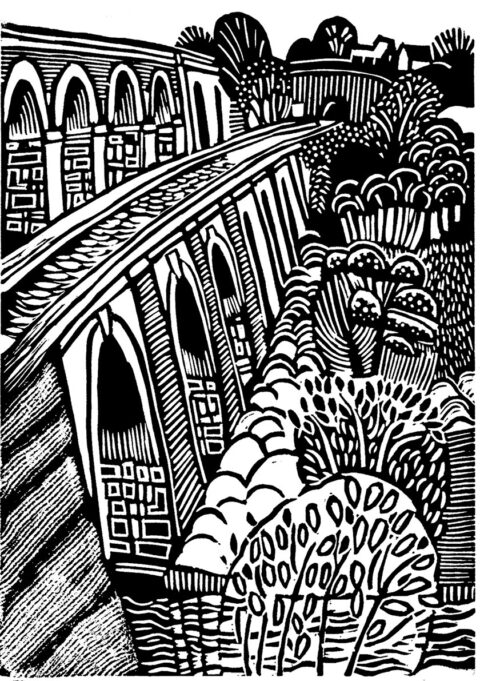

The canal continues to inspire modern artists, who capture it in many different media. Eric Gaskell is a professional artist and printmaker with a particular love for canals. He is a member of The Guild of Waterway Artists, a group especially devoted to promoting art featuring canals and rivers.

In 2016, people in Trevor and Froncysyllte were able to show their affection for the canal and the aqueduct linking them through a community painting project. Scenes from along the canal and throughout its history were created to decorate Froncysyllte Community Centre and the outside of a building near Trevor Basin.