LnRiLWZpZWxke21hcmdpbi1ib3R0b206MC43NmVtfS50Yi1maWVsZC0tbGVmdHt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOmxlZnR9LnRiLWZpZWxkLS1jZW50ZXJ7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjpjZW50ZXJ9LnRiLWZpZWxkLS1yaWdodHt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOnJpZ2h0fS50Yi1maWVsZF9fc2t5cGVfcHJldmlld3twYWRkaW5nOjEwcHggMjBweDtib3JkZXItcmFkaXVzOjNweDtjb2xvcjojZmZmO2JhY2tncm91bmQ6IzAwYWZlZTtkaXNwbGF5OmlubGluZS1ibG9ja311bC5nbGlkZV9fc2xpZGVze21hcmdpbjowfQ==

LnRiLWZpZWxkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZmllbGQ9IjJmNzVlZjY2OWZhNDcyZTAyOGEwMjdmYjExNzNhYzY2Il0geyBtYXJnaW4tYm90dG9tOiA1MHB4OyB9ICAudGItZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0PSIxMzg1NjQwYzQ2NjljY2ZmMTIyODgyYTE0YmVjMDBjYyJdIHsgbWFyZ2luLWJvdHRvbTogMjVweDsgfSAudGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyLS1jYXJvdXNlbHtvcGFjaXR5OjA7ZGlyZWN0aW9uOmx0cn0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fc2xpZGV7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6MH0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fc2xpZGUtLWNsb25le2N1cnNvcjpwb2ludGVyfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19zbGlkZSBpbWd7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtmbG9hdDpub25lICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX3ZpZXd7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOm9wYWNpdHkgMzUwbXMgZWFzZS1pbi1vdXQ7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmV9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX3ZpZXcgaW1ney1vLW9iamVjdC1maXQ6Y29udGFpbjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvbnRhaW47d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtmbG9hdDpub25lICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX3ZpZXctLWZhZGUtb3V0e29wYWNpdHk6MH0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fdmlldy0tZmFkZS1pbntvcGFjaXR5OjF9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93e2JvcmRlcjpub25lO3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO3otaW5kZXg6MTA7dG9wOjUwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmlubGluZS1mbGV4O2p1c3RpZnktY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXI7YWxpZ24taXRlbXM6Y2VudGVyO3dpZHRoOjQwcHg7aGVpZ2h0OjQwcHg7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjpjZW50ZXI7cGFkZGluZzowO2N1cnNvcjpwb2ludGVyO3RyYW5zZm9ybTp0cmFuc2xhdGVZKC01MCUpO2JvcmRlci1yYWRpdXM6NTBweDt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOmFsbCAwLjJzIGxpbmVhcjtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOnJnYmEoMjU1LDI1NSwyNTUsMC43KX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3c6Zm9jdXN7b3V0bGluZTpub25lO2JveC1zaGFkb3c6MCAwIDVweCAjNjY2O2JhY2tncm91bmQ6cmdiYSgyNTUsMjU1LDI1NSwwLjcpO29wYWNpdHk6MX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3c6aG92ZXJ7YmFja2dyb3VuZDpyZ2JhKDI1NSwyNTUsMjU1LDAuOSl9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93LS1sZWZ0e2xlZnQ6NXB4fS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19hcnJvdy0tbGVmdCBzdmd7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6LTFweH0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3ctLWxlZnQgc3Bhbi50Yi1zbGlkZXItbGVmdC1hcnJvd3tkaXNwbGF5OmlubGluZS1ibG9jazt3aWR0aDoyNXB4O2hlaWdodDoyNXB4O2JhY2tncm91bmQtaW1hZ2U6dXJsKCJkYXRhOmltYWdlL3N2Zyt4bWwsJTNDc3ZnIHhtbG5zPSdodHRwOi8vd3d3LnczLm9yZy8yMDAwL3N2Zycgdmlld0JveD0nMCAwIDEyOSAxMjknIHdpZHRoPScyNScgaGVpZ2h0PScyNSclM0UlM0NnJTNFJTNDcGF0aCBkPSdtNzAsOTMuNWMwLjgsMC44IDEuOCwxLjIgMi45LDEuMiAxLDAgMi4xLTAuNCAyLjktMS4yIDEuNi0xLjYgMS42LTQuMiAwLTUuOGwtMjMuNS0yMy41IDIzLjUtMjMuNWMxLjYtMS42IDEuNi00LjIgMC01LjhzLTQuMi0xLjYtNS44LDBsLTI2LjQsMjYuNGMtMC44LDAuOC0xLjIsMS44LTEuMiwyLjlzMC40LDIuMSAxLjIsMi45bDI2LjQsMjYuNHonIGZpbGw9JyUyMzY2NicvJTNFJTNDL2clM0UlM0Mvc3ZnJTNFIil9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93LS1yaWdodHtyaWdodDo1cHh9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93LS1yaWdodCBzdmd7bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0Oi0xcHh9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93LS1yaWdodCBzcGFuLnRiLXNsaWRlci1yaWdodC1hcnJvd3tkaXNwbGF5OmlubGluZS1ibG9jazt3aWR0aDoyNXB4O2hlaWdodDoyNXB4O2JhY2tncm91bmQtaW1hZ2U6dXJsKCJkYXRhOmltYWdlL3N2Zyt4bWwsJTNDc3ZnIHhtbG5zPSdodHRwOi8vd3d3LnczLm9yZy8yMDAwL3N2Zycgdmlld0JveD0nMCAwIDEyOSAxMjknIHdpZHRoPScyNScgaGVpZ2h0PScyNSclM0UlM0NnJTNFJTNDcGF0aCBkPSdtNTEuMSw5My41YzAuOCwwLjggMS44LDEuMiAyLjksMS4yIDEsMCAyLjEtMC40IDIuOS0xLjJsMjYuNC0yNi40YzAuOC0wLjggMS4yLTEuOCAxLjItMi45IDAtMS4xLTAuNC0yLjEtMS4yLTIuOWwtMjYuNC0yNi40Yy0xLjYtMS42LTQuMi0xLjYtNS44LDAtMS42LDEuNi0xLjYsNC4yIDAsNS44bDIzLjUsMjMuNS0yMy41LDIzLjVjLTEuNiwxLjYtMS42LDQuMiAwLDUuOHonIGZpbGw9JyUyMzY2NicvJTNFJTNDL2clM0UlM0Mvc3ZnJTNFIil9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGU6aG92ZXIgLmdsaWRlX19hcnJvdywudGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZTpmb2N1cyAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93e29wYWNpdHk6MX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyLS1jcm9wIC5nbGlkZV9fc2xpZGUgaW1ney1vLW9iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXI7b2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJSAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19zbGlkZXN7bGlzdC1zdHlsZS10eXBlOm5vbmU7cGFkZGluZy1sZWZ0OjA7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyX19jYXB0aW9ue3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO2JvdHRvbTowO3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7YmFja2dyb3VuZDpyZ2JhKDI1NSwyNTUsMjU1LDAuNik7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjpjZW50ZXI7Y29sb3I6IzMzM30udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyX19jYXB0aW9uIDplbXB0eXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOnRyYW5zcGFyZW50ICFpbXBvcnRhbnQ7bWFyZ2luOjA7cGFkZGluZzowfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXJfX2NhcHRpb24gZmlnY2FwdGlvbntwYWRkaW5nOjVweCAycHg7bWFyZ2luLXRvcDo1cHh9IC50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXI9ImVhZmNmNTU3ZmYyMGQ0ZDMyMGE5ZGFhNGZlZGM3MGYxIl0gLnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlci0tY2Fyb3VzZWwgeyBwYWRkaW5nLWJvdHRvbTogNTBweDsgfSAudGItZmllbGRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1maWVsZD0iMWM1MWVhZGU0OTgyY2I1OTg0MzJkMjE2ZmQ2NjBmMWEiXSB7IHBhZGRpbmctYm90dG9tOiAzMHB4OyB9ICBAbWVkaWEgb25seSBzY3JlZW4gYW5kIChtYXgtd2lkdGg6IDc4MXB4KSB7ICAudGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyLS1jYXJvdXNlbHtvcGFjaXR5OjA7ZGlyZWN0aW9uOmx0cn0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fc2xpZGV7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6MH0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fc2xpZGUtLWNsb25le2N1cnNvcjpwb2ludGVyfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19zbGlkZSBpbWd7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtmbG9hdDpub25lICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX3ZpZXd7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOm9wYWNpdHkgMzUwbXMgZWFzZS1pbi1vdXQ7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmV9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX3ZpZXcgaW1ney1vLW9iamVjdC1maXQ6Y29udGFpbjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvbnRhaW47d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtmbG9hdDpub25lICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX3ZpZXctLWZhZGUtb3V0e29wYWNpdHk6MH0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fdmlldy0tZmFkZS1pbntvcGFjaXR5OjF9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93e2JvcmRlcjpub25lO3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO3otaW5kZXg6MTA7dG9wOjUwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmlubGluZS1mbGV4O2p1c3RpZnktY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXI7YWxpZ24taXRlbXM6Y2VudGVyO3dpZHRoOjQwcHg7aGVpZ2h0OjQwcHg7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjpjZW50ZXI7cGFkZGluZzowO2N1cnNvcjpwb2ludGVyO3RyYW5zZm9ybTp0cmFuc2xhdGVZKC01MCUpO2JvcmRlci1yYWRpdXM6NTBweDt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOmFsbCAwLjJzIGxpbmVhcjtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOnJnYmEoMjU1LDI1NSwyNTUsMC43KX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3c6Zm9jdXN7b3V0bGluZTpub25lO2JveC1zaGFkb3c6MCAwIDVweCAjNjY2O2JhY2tncm91bmQ6cmdiYSgyNTUsMjU1LDI1NSwwLjcpO29wYWNpdHk6MX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3c6aG92ZXJ7YmFja2dyb3VuZDpyZ2JhKDI1NSwyNTUsMjU1LDAuOSl9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93LS1sZWZ0e2xlZnQ6NXB4fS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19hcnJvdy0tbGVmdCBzdmd7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6LTFweH0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3ctLWxlZnQgc3Bhbi50Yi1zbGlkZXItbGVmdC1hcnJvd3tkaXNwbGF5OmlubGluZS1ibG9jazt3aWR0aDoyNXB4O2hlaWdodDoyNXB4O2JhY2tncm91bmQtaW1hZ2U6dXJsKCJkYXRhOmltYWdlL3N2Zyt4bWwsJTNDc3ZnIHhtbG5zPSdodHRwOi8vd3d3LnczLm9yZy8yMDAwL3N2Zycgdmlld0JveD0nMCAwIDEyOSAxMjknIHdpZHRoPScyNScgaGVpZ2h0PScyNSclM0UlM0NnJTNFJTNDcGF0aCBkPSdtNzAsOTMuNWMwLjgsMC44IDEuOCwxLjIgMi45LDEuMiAxLDAgMi4xLTAuNCAyLjktMS4yIDEuNi0xLjYgMS42LTQuMiAwLTUuOGwtMjMuNS0yMy41IDIzLjUtMjMuNWMxLjYtMS42IDEuNi00LjIgMC01LjhzLTQuMi0xLjYtNS44LDBsLTI2LjQsMjYuNGMtMC44LDAuOC0xLjIsMS44LTEuMiwyLjlzMC40LDIuMSAxLjIsMi45bDI2LjQsMjYuNHonIGZpbGw9JyUyMzY2NicvJTNFJTNDL2clM0UlM0Mvc3ZnJTNFIil9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93LS1yaWdodHtyaWdodDo1cHh9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93LS1yaWdodCBzdmd7bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0Oi0xcHh9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93LS1yaWdodCBzcGFuLnRiLXNsaWRlci1yaWdodC1hcnJvd3tkaXNwbGF5OmlubGluZS1ibG9jazt3aWR0aDoyNXB4O2hlaWdodDoyNXB4O2JhY2tncm91bmQtaW1hZ2U6dXJsKCJkYXRhOmltYWdlL3N2Zyt4bWwsJTNDc3ZnIHhtbG5zPSdodHRwOi8vd3d3LnczLm9yZy8yMDAwL3N2Zycgdmlld0JveD0nMCAwIDEyOSAxMjknIHdpZHRoPScyNScgaGVpZ2h0PScyNSclM0UlM0NnJTNFJTNDcGF0aCBkPSdtNTEuMSw5My41YzAuOCwwLjggMS44LDEuMiAyLjksMS4yIDEsMCAyLjEtMC40IDIuOS0xLjJsMjYuNC0yNi40YzAuOC0wLjggMS4yLTEuOCAxLjItMi45IDAtMS4xLTAuNC0yLjEtMS4yLTIuOWwtMjYuNC0yNi40Yy0xLjYtMS42LTQuMi0xLjYtNS44LDAtMS42LDEuNi0xLjYsNC4yIDAsNS44bDIzLjUsMjMuNS0yMy41LDIzLjVjLTEuNiwxLjYtMS42LDQuMiAwLDUuOHonIGZpbGw9JyUyMzY2NicvJTNFJTNDL2clM0UlM0Mvc3ZnJTNFIil9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGU6aG92ZXIgLmdsaWRlX19hcnJvdywudGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZTpmb2N1cyAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93e29wYWNpdHk6MX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyLS1jcm9wIC5nbGlkZV9fc2xpZGUgaW1ney1vLW9iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXI7b2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJSAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19zbGlkZXN7bGlzdC1zdHlsZS10eXBlOm5vbmU7cGFkZGluZy1sZWZ0OjA7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyX19jYXB0aW9ue3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO2JvdHRvbTowO3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7YmFja2dyb3VuZDpyZ2JhKDI1NSwyNTUsMjU1LDAuNik7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjpjZW50ZXI7Y29sb3I6IzMzM30udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyX19jYXB0aW9uIDplbXB0eXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOnRyYW5zcGFyZW50ICFpbXBvcnRhbnQ7bWFyZ2luOjA7cGFkZGluZzowfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXJfX2NhcHRpb24gZmlnY2FwdGlvbntwYWRkaW5nOjVweCAycHg7bWFyZ2luLXRvcDo1cHh9ICB9IEBtZWRpYSBvbmx5IHNjcmVlbiBhbmQgKG1heC13aWR0aDogNTk5cHgpIHsgIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXItLWNhcm91c2Vse29wYWNpdHk6MDtkaXJlY3Rpb246bHRyfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19zbGlkZXtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bztwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZTttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDowfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19zbGlkZS0tY2xvbmV7Y3Vyc29yOnBvaW50ZXJ9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX3NsaWRlIGltZ3t3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Zsb2F0Om5vbmUgIWltcG9ydGFudH0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fdmlld3t3aWR0aDoxMDAlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246b3BhY2l0eSAzNTBtcyBlYXNlLWluLW91dDtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fdmlldyBpbWd7LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb250YWluO29iamVjdC1maXQ6Y29udGFpbjt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Zsb2F0Om5vbmUgIWltcG9ydGFudH0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fdmlldy0tZmFkZS1vdXR7b3BhY2l0eTowfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX192aWV3LS1mYWRlLWlue29wYWNpdHk6MX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3d7Ym9yZGVyOm5vbmU7cG9zaXRpb246YWJzb2x1dGU7ei1pbmRleDoxMDt0b3A6NTAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6aW5saW5lLWZsZXg7anVzdGlmeS1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcjthbGlnbi1pdGVtczpjZW50ZXI7d2lkdGg6NDBweDtoZWlnaHQ6NDBweDt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOmNlbnRlcjtwYWRkaW5nOjA7Y3Vyc29yOnBvaW50ZXI7dHJhbnNmb3JtOnRyYW5zbGF0ZVkoLTUwJSk7Ym9yZGVyLXJhZGl1czo1MHB4O3RyYW5zaXRpb246YWxsIDAuMnMgbGluZWFyO2JhY2tncm91bmQ6cmdiYSgyNTUsMjU1LDI1NSwwLjcpfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19hcnJvdzpmb2N1c3tvdXRsaW5lOm5vbmU7Ym94LXNoYWRvdzowIDAgNXB4ICM2NjY7YmFja2dyb3VuZDpyZ2JhKDI1NSwyNTUsMjU1LDAuNyk7b3BhY2l0eToxfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19hcnJvdzpob3ZlcntiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOnJnYmEoMjU1LDI1NSwyNTUsMC45KX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3ctLWxlZnR7bGVmdDo1cHh9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93LS1sZWZ0IHN2Z3ttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDotMXB4fS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19hcnJvdy0tbGVmdCBzcGFuLnRiLXNsaWRlci1sZWZ0LWFycm93e2Rpc3BsYXk6aW5saW5lLWJsb2NrO3dpZHRoOjI1cHg7aGVpZ2h0OjI1cHg7YmFja2dyb3VuZC1pbWFnZTp1cmwoImRhdGE6aW1hZ2Uvc3ZnK3htbCwlM0NzdmcgeG1sbnM9J2h0dHA6Ly93d3cudzMub3JnLzIwMDAvc3ZnJyB2aWV3Qm94PScwIDAgMTI5IDEyOScgd2lkdGg9JzI1JyBoZWlnaHQ9JzI1JyUzRSUzQ2clM0UlM0NwYXRoIGQ9J203MCw5My41YzAuOCwwLjggMS44LDEuMiAyLjksMS4yIDEsMCAyLjEtMC40IDIuOS0xLjIgMS42LTEuNiAxLjYtNC4yIDAtNS44bC0yMy41LTIzLjUgMjMuNS0yMy41YzEuNi0xLjYgMS42LTQuMiAwLTUuOHMtNC4yLTEuNi01LjgsMGwtMjYuNCwyNi40Yy0wLjgsMC44LTEuMiwxLjgtMS4yLDIuOXMwLjQsMi4xIDEuMiwyLjlsMjYuNCwyNi40eicgZmlsbD0nJTIzNjY2Jy8lM0UlM0MvZyUzRSUzQy9zdmclM0UiKX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3ctLXJpZ2h0e3JpZ2h0OjVweH0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3ctLXJpZ2h0IHN2Z3ttYXJnaW4tcmlnaHQ6LTFweH0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3ctLXJpZ2h0IHNwYW4udGItc2xpZGVyLXJpZ2h0LWFycm93e2Rpc3BsYXk6aW5saW5lLWJsb2NrO3dpZHRoOjI1cHg7aGVpZ2h0OjI1cHg7YmFja2dyb3VuZC1pbWFnZTp1cmwoImRhdGE6aW1hZ2Uvc3ZnK3htbCwlM0NzdmcgeG1sbnM9J2h0dHA6Ly93d3cudzMub3JnLzIwMDAvc3ZnJyB2aWV3Qm94PScwIDAgMTI5IDEyOScgd2lkdGg9JzI1JyBoZWlnaHQ9JzI1JyUzRSUzQ2clM0UlM0NwYXRoIGQ9J201MS4xLDkzLjVjMC44LDAuOCAxLjgsMS4yIDIuOSwxLjIgMSwwIDIuMS0wLjQgMi45LTEuMmwyNi40LTI2LjRjMC44LTAuOCAxLjItMS44IDEuMi0yLjkgMC0xLjEtMC40LTIuMS0xLjItMi45bC0yNi40LTI2LjRjLTEuNi0xLjYtNC4yLTEuNi01LjgsMC0xLjYsMS42LTEuNiw0LjIgMCw1LjhsMjMuNSwyMy41LTIzLjUsMjMuNWMtMS42LDEuNi0xLjYsNC4yIDAsNS44eicgZmlsbD0nJTIzNjY2Jy8lM0UlM0MvZyUzRSUzQy9zdmclM0UiKX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZTpob3ZlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93LC50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlOmZvY3VzIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3d7b3BhY2l0eToxfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXItLWNyb3AgLmdsaWRlX19zbGlkZSBpbWd7LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO2hlaWdodDoxMDAlICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX3NsaWRlc3tsaXN0LXN0eWxlLXR5cGU6bm9uZTtwYWRkaW5nLWxlZnQ6MDttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXJfX2NhcHRpb257cG9zaXRpb246YWJzb2x1dGU7Ym90dG9tOjA7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOnJnYmEoMjU1LDI1NSwyNTUsMC42KTt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOmNlbnRlcjtjb2xvcjojMzMzfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXJfX2NhcHRpb24gOmVtcHR5e2JhY2tncm91bmQ6dHJhbnNwYXJlbnQgIWltcG9ydGFudDttYXJnaW46MDtwYWRkaW5nOjB9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlcl9fY2FwdGlvbiBmaWdjYXB0aW9ue3BhZGRpbmc6NXB4IDJweDttYXJnaW4tdG9wOjVweH0gIH0g

The village of Cefn Mawr can be seen clearly from the Pontcysyllte aqueduct, on a prominent hill to the east. The hill is a ridge of sandstone. From here, quarries supplied excellent building stone to make the tall, slender piers that support the aqueduct across the Dee valley.

The best quality stone from Cefn Mawr had been used for building grand houses and important buildings in the area since the Middle Ages. As industry made the village richer, cottages and shops were built of it too. The stone is a pale yellow when it is first cut but it weathers to a rich golden colour after a few years.

Cefn Stone is hard-wearing but can be cut precisely to make a perfect fit between every block. The engineers Thomas Telford and William Jessop recognised its quality when they were building the canal. They used it to construct Chirk Aqueduct. It was also the natural choice for Pontcysyllte Aqueduct.

The fame of Cefn Stone spread beyond the local area. By 1845 as much as 1,000 tons were being transported from the quarries each year, much of it by canal. Eventually the quarries became depleted of the best stone and closed.

LnRiLWZpZWxkW2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZmllbGQ9IjJmNzVlZjY2OWZhNDcyZTAyOGEwMjdmYjExNzNhYzY2Il0geyBtYXJnaW4tYm90dG9tOiA1MHB4OyB9ICAudGItZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0W2RhdGEtdG9vbHNldC1ibG9ja3MtZmllbGRzLWFuZC10ZXh0PSIxMzg1NjQwYzQ2NjljY2ZmMTIyODgyYTE0YmVjMDBjYyJdIHsgbWFyZ2luLWJvdHRvbTogMjVweDsgfSAudGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyLS1jYXJvdXNlbHtvcGFjaXR5OjA7ZGlyZWN0aW9uOmx0cn0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fc2xpZGV7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6MH0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fc2xpZGUtLWNsb25le2N1cnNvcjpwb2ludGVyfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19zbGlkZSBpbWd7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtmbG9hdDpub25lICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX3ZpZXd7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOm9wYWNpdHkgMzUwbXMgZWFzZS1pbi1vdXQ7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmV9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX3ZpZXcgaW1ney1vLW9iamVjdC1maXQ6Y29udGFpbjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvbnRhaW47d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtmbG9hdDpub25lICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX3ZpZXctLWZhZGUtb3V0e29wYWNpdHk6MH0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fdmlldy0tZmFkZS1pbntvcGFjaXR5OjF9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93e2JvcmRlcjpub25lO3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO3otaW5kZXg6MTA7dG9wOjUwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmlubGluZS1mbGV4O2p1c3RpZnktY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXI7YWxpZ24taXRlbXM6Y2VudGVyO3dpZHRoOjQwcHg7aGVpZ2h0OjQwcHg7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjpjZW50ZXI7cGFkZGluZzowO2N1cnNvcjpwb2ludGVyO3RyYW5zZm9ybTp0cmFuc2xhdGVZKC01MCUpO2JvcmRlci1yYWRpdXM6NTBweDt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOmFsbCAwLjJzIGxpbmVhcjtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOnJnYmEoMjU1LDI1NSwyNTUsMC43KX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3c6Zm9jdXN7b3V0bGluZTpub25lO2JveC1zaGFkb3c6MCAwIDVweCAjNjY2O2JhY2tncm91bmQ6cmdiYSgyNTUsMjU1LDI1NSwwLjcpO29wYWNpdHk6MX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3c6aG92ZXJ7YmFja2dyb3VuZDpyZ2JhKDI1NSwyNTUsMjU1LDAuOSl9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93LS1sZWZ0e2xlZnQ6NXB4fS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19hcnJvdy0tbGVmdCBzdmd7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6LTFweH0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3ctLWxlZnQgc3Bhbi50Yi1zbGlkZXItbGVmdC1hcnJvd3tkaXNwbGF5OmlubGluZS1ibG9jazt3aWR0aDoyNXB4O2hlaWdodDoyNXB4O2JhY2tncm91bmQtaW1hZ2U6dXJsKCJkYXRhOmltYWdlL3N2Zyt4bWwsJTNDc3ZnIHhtbG5zPSdodHRwOi8vd3d3LnczLm9yZy8yMDAwL3N2Zycgdmlld0JveD0nMCAwIDEyOSAxMjknIHdpZHRoPScyNScgaGVpZ2h0PScyNSclM0UlM0NnJTNFJTNDcGF0aCBkPSdtNzAsOTMuNWMwLjgsMC44IDEuOCwxLjIgMi45LDEuMiAxLDAgMi4xLTAuNCAyLjktMS4yIDEuNi0xLjYgMS42LTQuMiAwLTUuOGwtMjMuNS0yMy41IDIzLjUtMjMuNWMxLjYtMS42IDEuNi00LjIgMC01LjhzLTQuMi0xLjYtNS44LDBsLTI2LjQsMjYuNGMtMC44LDAuOC0xLjIsMS44LTEuMiwyLjlzMC40LDIuMSAxLjIsMi45bDI2LjQsMjYuNHonIGZpbGw9JyUyMzY2NicvJTNFJTNDL2clM0UlM0Mvc3ZnJTNFIil9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93LS1yaWdodHtyaWdodDo1cHh9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93LS1yaWdodCBzdmd7bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0Oi0xcHh9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93LS1yaWdodCBzcGFuLnRiLXNsaWRlci1yaWdodC1hcnJvd3tkaXNwbGF5OmlubGluZS1ibG9jazt3aWR0aDoyNXB4O2hlaWdodDoyNXB4O2JhY2tncm91bmQtaW1hZ2U6dXJsKCJkYXRhOmltYWdlL3N2Zyt4bWwsJTNDc3ZnIHhtbG5zPSdodHRwOi8vd3d3LnczLm9yZy8yMDAwL3N2Zycgdmlld0JveD0nMCAwIDEyOSAxMjknIHdpZHRoPScyNScgaGVpZ2h0PScyNSclM0UlM0NnJTNFJTNDcGF0aCBkPSdtNTEuMSw5My41YzAuOCwwLjggMS44LDEuMiAyLjksMS4yIDEsMCAyLjEtMC40IDIuOS0xLjJsMjYuNC0yNi40YzAuOC0wLjggMS4yLTEuOCAxLjItMi45IDAtMS4xLTAuNC0yLjEtMS4yLTIuOWwtMjYuNC0yNi40Yy0xLjYtMS42LTQuMi0xLjYtNS44LDAtMS42LDEuNi0xLjYsNC4yIDAsNS44bDIzLjUsMjMuNS0yMy41LDIzLjVjLTEuNiwxLjYtMS42LDQuMiAwLDUuOHonIGZpbGw9JyUyMzY2NicvJTNFJTNDL2clM0UlM0Mvc3ZnJTNFIil9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGU6aG92ZXIgLmdsaWRlX19hcnJvdywudGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZTpmb2N1cyAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93e29wYWNpdHk6MX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyLS1jcm9wIC5nbGlkZV9fc2xpZGUgaW1ney1vLW9iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXI7b2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJSAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19zbGlkZXN7bGlzdC1zdHlsZS10eXBlOm5vbmU7cGFkZGluZy1sZWZ0OjA7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyX19jYXB0aW9ue3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO2JvdHRvbTowO3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7YmFja2dyb3VuZDpyZ2JhKDI1NSwyNTUsMjU1LDAuNik7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjpjZW50ZXI7Y29sb3I6IzMzM30udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyX19jYXB0aW9uIDplbXB0eXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOnRyYW5zcGFyZW50ICFpbXBvcnRhbnQ7bWFyZ2luOjA7cGFkZGluZzowfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXJfX2NhcHRpb24gZmlnY2FwdGlvbntwYWRkaW5nOjVweCAycHg7bWFyZ2luLXRvcDo1cHh9IC50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXJbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXI9ImVhZmNmNTU3ZmYyMGQ0ZDMyMGE5ZGFhNGZlZGM3MGYxIl0gLnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlci0tY2Fyb3VzZWwgeyBwYWRkaW5nLWJvdHRvbTogNTBweDsgfSAudGItZmllbGRbZGF0YS10b29sc2V0LWJsb2Nrcy1maWVsZD0iMWM1MWVhZGU0OTgyY2I1OTg0MzJkMjE2ZmQ2NjBmMWEiXSB7IHBhZGRpbmctYm90dG9tOiAzMHB4OyB9ICBAbWVkaWEgb25seSBzY3JlZW4gYW5kIChtYXgtd2lkdGg6IDc4MXB4KSB7ICAudGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyLS1jYXJvdXNlbHtvcGFjaXR5OjA7ZGlyZWN0aW9uOmx0cn0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZXtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fc2xpZGV7aGVpZ2h0OmF1dG87cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmU7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6MH0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fc2xpZGUtLWNsb25le2N1cnNvcjpwb2ludGVyfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19zbGlkZSBpbWd7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtmbG9hdDpub25lICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX3ZpZXd7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOm9wYWNpdHkgMzUwbXMgZWFzZS1pbi1vdXQ7cG9zaXRpb246cmVsYXRpdmV9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX3ZpZXcgaW1ney1vLW9iamVjdC1maXQ6Y29udGFpbjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvbnRhaW47d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtmbG9hdDpub25lICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX3ZpZXctLWZhZGUtb3V0e29wYWNpdHk6MH0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fdmlldy0tZmFkZS1pbntvcGFjaXR5OjF9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93e2JvcmRlcjpub25lO3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO3otaW5kZXg6MTA7dG9wOjUwJTtkaXNwbGF5OmlubGluZS1mbGV4O2p1c3RpZnktY29udGVudDpjZW50ZXI7YWxpZ24taXRlbXM6Y2VudGVyO3dpZHRoOjQwcHg7aGVpZ2h0OjQwcHg7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjpjZW50ZXI7cGFkZGluZzowO2N1cnNvcjpwb2ludGVyO3RyYW5zZm9ybTp0cmFuc2xhdGVZKC01MCUpO2JvcmRlci1yYWRpdXM6NTBweDt0cmFuc2l0aW9uOmFsbCAwLjJzIGxpbmVhcjtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOnJnYmEoMjU1LDI1NSwyNTUsMC43KX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3c6Zm9jdXN7b3V0bGluZTpub25lO2JveC1zaGFkb3c6MCAwIDVweCAjNjY2O2JhY2tncm91bmQ6cmdiYSgyNTUsMjU1LDI1NSwwLjcpO29wYWNpdHk6MX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3c6aG92ZXJ7YmFja2dyb3VuZDpyZ2JhKDI1NSwyNTUsMjU1LDAuOSl9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93LS1sZWZ0e2xlZnQ6NXB4fS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19hcnJvdy0tbGVmdCBzdmd7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6LTFweH0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3ctLWxlZnQgc3Bhbi50Yi1zbGlkZXItbGVmdC1hcnJvd3tkaXNwbGF5OmlubGluZS1ibG9jazt3aWR0aDoyNXB4O2hlaWdodDoyNXB4O2JhY2tncm91bmQtaW1hZ2U6dXJsKCJkYXRhOmltYWdlL3N2Zyt4bWwsJTNDc3ZnIHhtbG5zPSdodHRwOi8vd3d3LnczLm9yZy8yMDAwL3N2Zycgdmlld0JveD0nMCAwIDEyOSAxMjknIHdpZHRoPScyNScgaGVpZ2h0PScyNSclM0UlM0NnJTNFJTNDcGF0aCBkPSdtNzAsOTMuNWMwLjgsMC44IDEuOCwxLjIgMi45LDEuMiAxLDAgMi4xLTAuNCAyLjktMS4yIDEuNi0xLjYgMS42LTQuMiAwLTUuOGwtMjMuNS0yMy41IDIzLjUtMjMuNWMxLjYtMS42IDEuNi00LjIgMC01LjhzLTQuMi0xLjYtNS44LDBsLTI2LjQsMjYuNGMtMC44LDAuOC0xLjIsMS44LTEuMiwyLjlzMC40LDIuMSAxLjIsMi45bDI2LjQsMjYuNHonIGZpbGw9JyUyMzY2NicvJTNFJTNDL2clM0UlM0Mvc3ZnJTNFIil9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93LS1yaWdodHtyaWdodDo1cHh9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93LS1yaWdodCBzdmd7bWFyZ2luLXJpZ2h0Oi0xcHh9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93LS1yaWdodCBzcGFuLnRiLXNsaWRlci1yaWdodC1hcnJvd3tkaXNwbGF5OmlubGluZS1ibG9jazt3aWR0aDoyNXB4O2hlaWdodDoyNXB4O2JhY2tncm91bmQtaW1hZ2U6dXJsKCJkYXRhOmltYWdlL3N2Zyt4bWwsJTNDc3ZnIHhtbG5zPSdodHRwOi8vd3d3LnczLm9yZy8yMDAwL3N2Zycgdmlld0JveD0nMCAwIDEyOSAxMjknIHdpZHRoPScyNScgaGVpZ2h0PScyNSclM0UlM0NnJTNFJTNDcGF0aCBkPSdtNTEuMSw5My41YzAuOCwwLjggMS44LDEuMiAyLjksMS4yIDEsMCAyLjEtMC40IDIuOS0xLjJsMjYuNC0yNi40YzAuOC0wLjggMS4yLTEuOCAxLjItMi45IDAtMS4xLTAuNC0yLjEtMS4yLTIuOWwtMjYuNC0yNi40Yy0xLjYtMS42LTQuMi0xLjYtNS44LDAtMS42LDEuNi0xLjYsNC4yIDAsNS44bDIzLjUsMjMuNS0yMy41LDIzLjVjLTEuNiwxLjYtMS42LDQuMiAwLDUuOHonIGZpbGw9JyUyMzY2NicvJTNFJTNDL2clM0UlM0Mvc3ZnJTNFIil9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGU6aG92ZXIgLmdsaWRlX19hcnJvdywudGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZTpmb2N1cyAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93e29wYWNpdHk6MX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyLS1jcm9wIC5nbGlkZV9fc2xpZGUgaW1ney1vLW9iamVjdC1maXQ6Y292ZXI7b2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtoZWlnaHQ6MTAwJSAhaW1wb3J0YW50fS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19zbGlkZXN7bGlzdC1zdHlsZS10eXBlOm5vbmU7cGFkZGluZy1sZWZ0OjA7bWFyZ2luLWxlZnQ6YXV0b30udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyX19jYXB0aW9ue3Bvc2l0aW9uOmFic29sdXRlO2JvdHRvbTowO3dpZHRoOjEwMCU7YmFja2dyb3VuZDpyZ2JhKDI1NSwyNTUsMjU1LDAuNik7dGV4dC1hbGlnbjpjZW50ZXI7Y29sb3I6IzMzM30udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyX19jYXB0aW9uIDplbXB0eXtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOnRyYW5zcGFyZW50ICFpbXBvcnRhbnQ7bWFyZ2luOjA7cGFkZGluZzowfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXJfX2NhcHRpb24gZmlnY2FwdGlvbntwYWRkaW5nOjVweCAycHg7bWFyZ2luLXRvcDo1cHh9ICB9IEBtZWRpYSBvbmx5IHNjcmVlbiBhbmQgKG1heC13aWR0aDogNTk5cHgpIHsgIC50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXItLWNhcm91c2Vse29wYWNpdHk6MDtkaXJlY3Rpb246bHRyfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRle3Bvc2l0aW9uOnJlbGF0aXZlfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19zbGlkZXtoZWlnaHQ6YXV0bztwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZTttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDowfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19zbGlkZS0tY2xvbmV7Y3Vyc29yOnBvaW50ZXJ9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX3NsaWRlIGltZ3t3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Zsb2F0Om5vbmUgIWltcG9ydGFudH0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fdmlld3t3aWR0aDoxMDAlO3RyYW5zaXRpb246b3BhY2l0eSAzNTBtcyBlYXNlLWluLW91dDtwb3NpdGlvbjpyZWxhdGl2ZX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fdmlldyBpbWd7LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb250YWluO29iamVjdC1maXQ6Y29udGFpbjt3aWR0aDoxMDAlO2Zsb2F0Om5vbmUgIWltcG9ydGFudH0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fdmlldy0tZmFkZS1vdXR7b3BhY2l0eTowfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX192aWV3LS1mYWRlLWlue29wYWNpdHk6MX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3d7Ym9yZGVyOm5vbmU7cG9zaXRpb246YWJzb2x1dGU7ei1pbmRleDoxMDt0b3A6NTAlO2Rpc3BsYXk6aW5saW5lLWZsZXg7anVzdGlmeS1jb250ZW50OmNlbnRlcjthbGlnbi1pdGVtczpjZW50ZXI7d2lkdGg6NDBweDtoZWlnaHQ6NDBweDt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOmNlbnRlcjtwYWRkaW5nOjA7Y3Vyc29yOnBvaW50ZXI7dHJhbnNmb3JtOnRyYW5zbGF0ZVkoLTUwJSk7Ym9yZGVyLXJhZGl1czo1MHB4O3RyYW5zaXRpb246YWxsIDAuMnMgbGluZWFyO2JhY2tncm91bmQ6cmdiYSgyNTUsMjU1LDI1NSwwLjcpfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19hcnJvdzpmb2N1c3tvdXRsaW5lOm5vbmU7Ym94LXNoYWRvdzowIDAgNXB4ICM2NjY7YmFja2dyb3VuZDpyZ2JhKDI1NSwyNTUsMjU1LDAuNyk7b3BhY2l0eToxfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19hcnJvdzpob3ZlcntiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOnJnYmEoMjU1LDI1NSwyNTUsMC45KX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3ctLWxlZnR7bGVmdDo1cHh9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93LS1sZWZ0IHN2Z3ttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDotMXB4fS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlX19hcnJvdy0tbGVmdCBzcGFuLnRiLXNsaWRlci1sZWZ0LWFycm93e2Rpc3BsYXk6aW5saW5lLWJsb2NrO3dpZHRoOjI1cHg7aGVpZ2h0OjI1cHg7YmFja2dyb3VuZC1pbWFnZTp1cmwoImRhdGE6aW1hZ2Uvc3ZnK3htbCwlM0NzdmcgeG1sbnM9J2h0dHA6Ly93d3cudzMub3JnLzIwMDAvc3ZnJyB2aWV3Qm94PScwIDAgMTI5IDEyOScgd2lkdGg9JzI1JyBoZWlnaHQ9JzI1JyUzRSUzQ2clM0UlM0NwYXRoIGQ9J203MCw5My41YzAuOCwwLjggMS44LDEuMiAyLjksMS4yIDEsMCAyLjEtMC40IDIuOS0xLjIgMS42LTEuNiAxLjYtNC4yIDAtNS44bC0yMy41LTIzLjUgMjMuNS0yMy41YzEuNi0xLjYgMS42LTQuMiAwLTUuOHMtNC4yLTEuNi01LjgsMGwtMjYuNCwyNi40Yy0wLjgsMC44LTEuMiwxLjgtMS4yLDIuOXMwLjQsMi4xIDEuMiwyLjlsMjYuNCwyNi40eicgZmlsbD0nJTIzNjY2Jy8lM0UlM0MvZyUzRSUzQy9zdmclM0UiKX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3ctLXJpZ2h0e3JpZ2h0OjVweH0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3ctLXJpZ2h0IHN2Z3ttYXJnaW4tcmlnaHQ6LTFweH0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3ctLXJpZ2h0IHNwYW4udGItc2xpZGVyLXJpZ2h0LWFycm93e2Rpc3BsYXk6aW5saW5lLWJsb2NrO3dpZHRoOjI1cHg7aGVpZ2h0OjI1cHg7YmFja2dyb3VuZC1pbWFnZTp1cmwoImRhdGE6aW1hZ2Uvc3ZnK3htbCwlM0NzdmcgeG1sbnM9J2h0dHA6Ly93d3cudzMub3JnLzIwMDAvc3ZnJyB2aWV3Qm94PScwIDAgMTI5IDEyOScgd2lkdGg9JzI1JyBoZWlnaHQ9JzI1JyUzRSUzQ2clM0UlM0NwYXRoIGQ9J201MS4xLDkzLjVjMC44LDAuOCAxLjgsMS4yIDIuOSwxLjIgMSwwIDIuMS0wLjQgMi45LTEuMmwyNi40LTI2LjRjMC44LTAuOCAxLjItMS44IDEuMi0yLjkgMC0xLjEtMC40LTIuMS0xLjItMi45bC0yNi40LTI2LjRjLTEuNi0xLjYtNC4yLTEuNi01LjgsMC0xLjYsMS42LTEuNiw0LjIgMCw1LjhsMjMuNSwyMy41LTIzLjUsMjMuNWMtMS42LDEuNi0xLjYsNC4yIDAsNS44eicgZmlsbD0nJTIzNjY2Jy8lM0UlM0MvZyUzRSUzQy9zdmclM0UiKX0udGItaW1hZ2Utc2xpZGVyIC5nbGlkZTpob3ZlciAuZ2xpZGVfX2Fycm93LC50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXIgLmdsaWRlOmZvY3VzIC5nbGlkZV9fYXJyb3d7b3BhY2l0eToxfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXItLWNyb3AgLmdsaWRlX19zbGlkZSBpbWd7LW8tb2JqZWN0LWZpdDpjb3ZlcjtvYmplY3QtZml0OmNvdmVyO2hlaWdodDoxMDAlICFpbXBvcnRhbnR9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlciAuZ2xpZGVfX3NsaWRlc3tsaXN0LXN0eWxlLXR5cGU6bm9uZTtwYWRkaW5nLWxlZnQ6MDttYXJnaW4tbGVmdDphdXRvfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXJfX2NhcHRpb257cG9zaXRpb246YWJzb2x1dGU7Ym90dG9tOjA7d2lkdGg6MTAwJTtiYWNrZ3JvdW5kOnJnYmEoMjU1LDI1NSwyNTUsMC42KTt0ZXh0LWFsaWduOmNlbnRlcjtjb2xvcjojMzMzfS50Yi1pbWFnZS1zbGlkZXJfX2NhcHRpb24gOmVtcHR5e2JhY2tncm91bmQ6dHJhbnNwYXJlbnQgIWltcG9ydGFudDttYXJnaW46MDtwYWRkaW5nOjB9LnRiLWltYWdlLXNsaWRlcl9fY2FwdGlvbiBmaWdjYXB0aW9ue3BhZGRpbmc6NXB4IDJweDttYXJnaW4tdG9wOjVweH0gIH0g

Sandstone was originally the sandy bed of ancient river deltas. Over millions of years the sand was heated and compressed into rock by the weight of more layers forming on top. Sandstone has a high quartz crystal content, which makes it hard-wearing and gives it a rough, gritty surface.

Sandstone boulder ©Andrew Deathe

The sandstone was hand-worked from the quarry faces. Workmen chiselled and drilled into the rock to create cracks. Wedges were hammered into the cracks, splitting the huge blocks of stone from the cliffs. In the old quarries it is still possible to see chisel marks made over a century ago.

Tan y Graig quarry chisel marks ©Andrew Deathe

The main streets of Cefn Mawr wind around the edge of the sandstone ridge. Many of the shops, pubs and houses are built onto terraces which were cut into the rock when the stone was quarried away. Buildings are sometimes squeezed into small spaces and unusual angles.

Cefn Mawr street: Courtesy of Cefn Mawr Museum

Minshall’s Croft is one of many narrow, steep lanes in Cefn Mawr. Originally, they were inclines – sloping railways that took stone from quarries down to the more level, horse-drawn tramroads. These took the stone to masonry yards for cutting and shaping, then onwards to the canal or railway for transport.

Minshall’s Croft ©Crown copyright: RCAHMW

The area around Cefn Mawr also has excellent clay for brickmaking. By the mid-nineteenth century bricks became much cheaper to produce than stone. Stone was only used locally for important buildings, or exported for prestigious projects elsewhere. Around Cefn Mawr, it’s easy to find buildings that use both materials.

Brick and sandstone building ©Andrew Deathe

Many of the quarries in Cefn Mawr have all but disappeared under later buildings but one is still partially open. The owner of Tan y Graig is using freshly cut stone from the quarry to build new houses on the site. A few nineteenth century quarry workers’ cottages still stand in the quarry as well.

Tan y Graig quarry ©Andrew Deathe

Some of the disused quarries around Cefn Mawr have been reclaimed as woodland and parks. The local football team, Cefn Druids, moved their ground to The Rock in 2010 and now play under a spectacular backdrop of former quarry cliffs.

The Rock football ground ©weallstandtogether.blogspot.com

When Pontcysyllte Aqueduct was built, each pier was raised a few metres high, before a wooden platform was constructed between them all to make a working level for the next height. Holes showing where the platform supports were clamped to the stonework can still be seen.

Platform scaffold holes in aqueduct ©Andrew Deathe

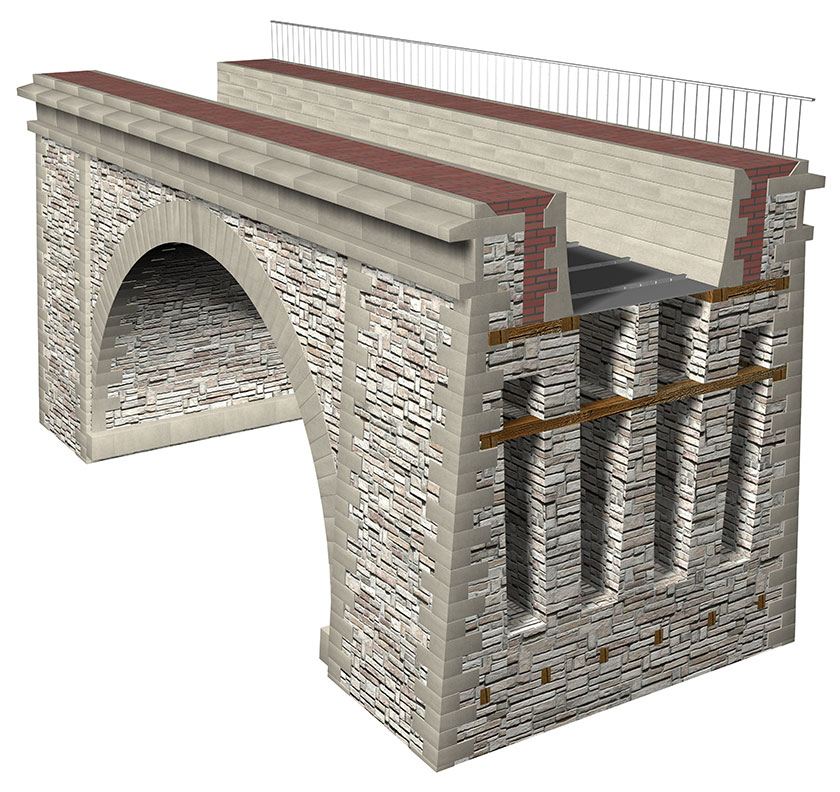

The upper parts of the piers of Chirk and Pontcysyllte Aqueducts are hollow. Jessop and Telford designed them this way so that they would still support the weight above them but the piers themselves would be as light as possible. At Chirk, maintenance holes in the arches allow access to the inside of the piers.

Hollow Chirk Aqueduct model ©Crown copyright: RCAHMW

Man entering Chirk Aqueduct ©Harry Arnold WATERWAY IMAGES

The Cefn Stone used at Pontcysyllte Aqueduct has lasted very well for over 200 years. A few blocks just below the canal trough had been damaged by water, however. These were replaced in 2003 with stone from the original quarries. They are a lighter colour now but in time they will weather like the older blocks.

New stone block in Pontcysyllte Aqueduct ©Andrew Deathe

Each surface of the Cefn Stone blocks was given a rough texture by the masons. The stones won’t slip against each other, so only a thin layer of mortar is needed between them. The mortar was made of lime, water and ox blood. The blood increases the mortar’s resistance to temperature changes.

Detail of masonry at Pontcysyllte Aqueduct ©Andrew Deathe

St Giles Church in Wrexham is one of the most important medieval buildings in Wales. It was built from Cefn Sandstone in the fifteenth century, showing how long the stone has been prized for its building quality. Coincidentally, the church tower is almost the same height as Pontcysyllte Aqueduct.

St Giles, Wrexham ©Jeff Buck / St Giles’ Church, Wrexham / CC BY-SA 2.0

Cefn Stone was so highly prized as a building stone that it was exported long distances for important buildings. In Bangor the prominent university building is built from it. In Liverpool the Walker Art Gallery and St George’s Hall are both built mainly from Cefn Stone.

St George’s Hall, Liverpool ©Tony Hisgett