Description

Canals provided employment for tens of thousands of people in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As well as the industries served by the transport network, the canal companies needed maintenance teams, wharf and warehouse managers and of course boat operators.

At first, boatmen lived in houses near the canals. As the canal network spread across Britain, many undertook longer journeys and spent more time on their boats. Competition from railways resulted in carrying companies reducing their charges; boatmen’s incomes fell too. It became cheaper for boatmen to have their families with them. A close-knit community of boat people grew from the lifestyle, with a shared culture coloured by different regional traditions.

Most boatmen worked for carrying companies. ‘Number ones’ were boatmen who owned or leased their boat. Both were usually paid according to the miles travelled or the tons carried. In turn they then employed the crew or family members.

It’s easy to romanticise life on the canals but the work was hard, with long hours, physical labour and through all weathers. Everyone in the family was expected to help out, including young children. By the 1960s nearly all working boats had disappeared from the canals, and the boat people with them.

Idle women

During the 1940s, more than 600 families still lived and worked on the waterways. Joining them in support of the war effort were around 45 women working for Inland Waterways, whose initials earned them the nickname ‘Idle Women’. They learned to work narrow boats and delivered coal around the Midlands from 1943-46.

Sign writer

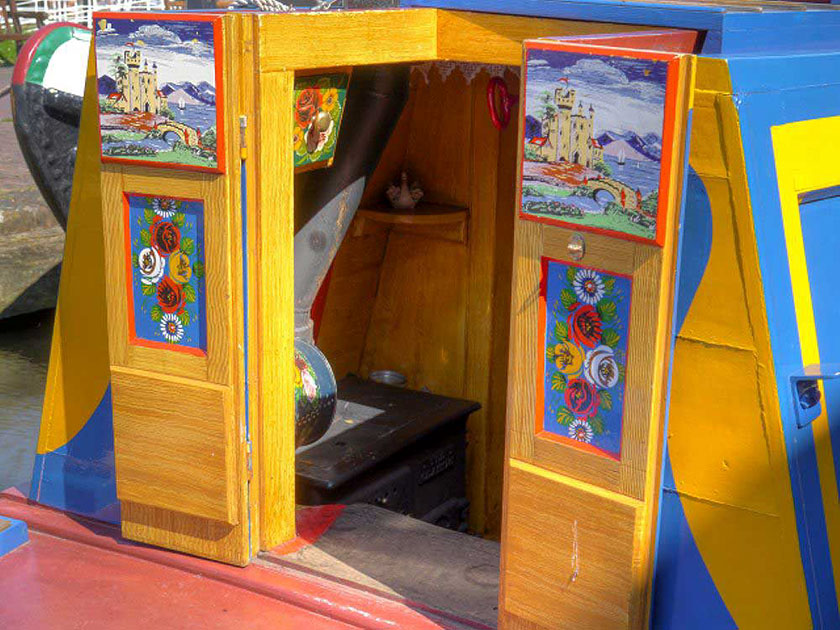

The canals still support many businesses alongside the water. As well as many boat hire companies, there are boat builders and repairers, specialist electricians, plumbers and mechanics as well as shops selling equipment. Graham Brown is a signwriter and narrowboat painter, who has worked for many years around Gloucester.

More Information About Life on the canal

What we know as the Llangollen Canal started life as the Ellesmere Canal, became the Ellesmere & Chester Canal and then formed part of the Shropshire Union Canal. Each company displayed their name or initials on company property, from boats to horse harnesses, or to tools such as this weight.

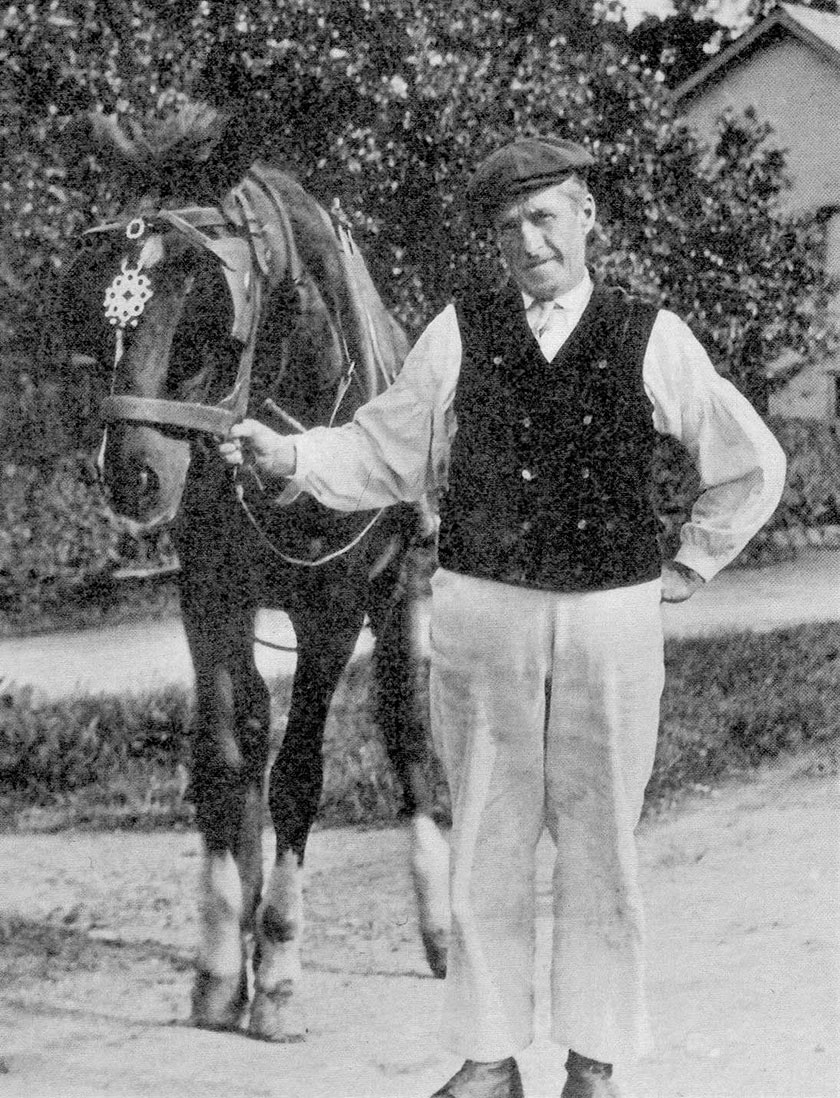

Although there was no strictly enforced uniform for workers on the Shropshire Union Canal, the boatmen developed a distinctive style of clothing, with white corduroy trousers, a blue waistcoat and blue socks. They also wore a blue and white, or black neckerchief and decorated their belts with small brass ornaments.

In the mid-nineteenth century, canal companies built workers’ houses along the banks. Some housed boatmen and others maintenance staff. Houses were built next to locks for lock keepers. In the later nineteenth century, houses were built for lengthsmen, who patrolled and maintained stretches of the towpath. This one is at Froncysyllte.

Wharves, where goods were loaded and unloaded, were busy places and the managers, known as wharfingers, often lived onsite. This cottage was originally a canal company office and then a wharfinger’s house, beside the busy junction of Trevor basin, Plas Kynaston Canal and the many tramroads serving industries around Cefn Mawr.

When the first canals opened at the end of the eighteenth century, journeys were relatively short. Boatmen were rarely away for more than one night and they would return most days to where their families were settled. The houses were often small, such as these 1820 cottages at Canal View, Chirk Bank.

As the canal network grew across Britain, journeys could become much longer, sometimes for weeks at a time. From the middle of the nineteenth century, many boatmen’s families lived with them aboard the boats. Constantly moving around and dealing mainly with others in the same situation, a boating culture developed.

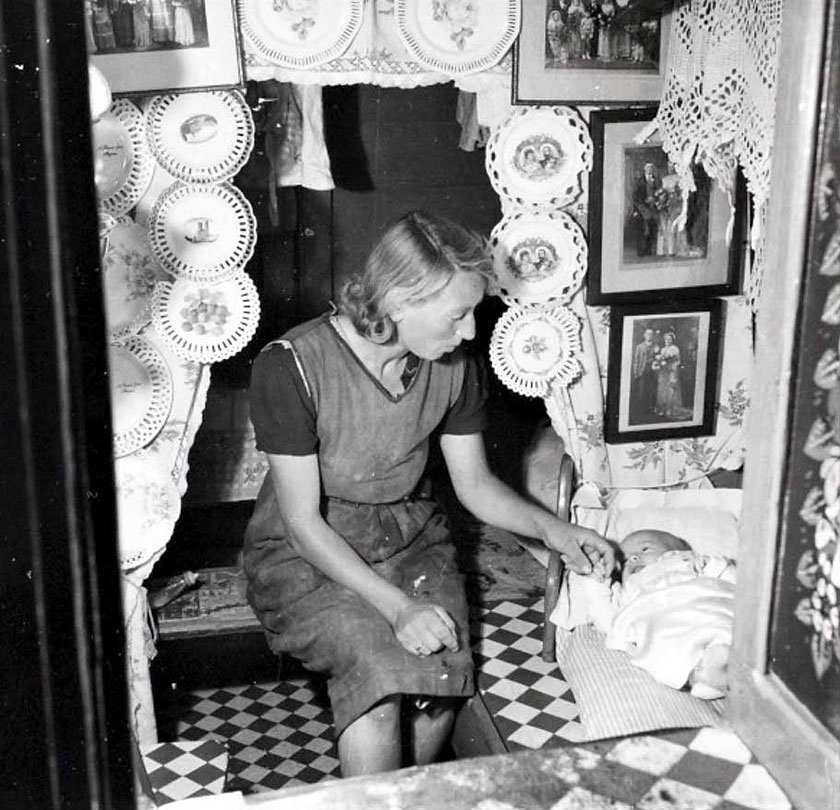

Living space on board a narrow boat was very small. Room for cargo, which paid the boat operators was considered to be more important. It was not uncommon for families of five or more to live in just a few square metres of cabin that served as bedroom, kitchen and living room.

Boatwomen had busy lives, keeping the stove burning, cooking, washing clothes and looking after children, as well as helping to manage the boat at locks and wharves. They took pride in keeping the cabins clean but it was difficult when cargoes were usually dirty and there were very limited washing facilities.

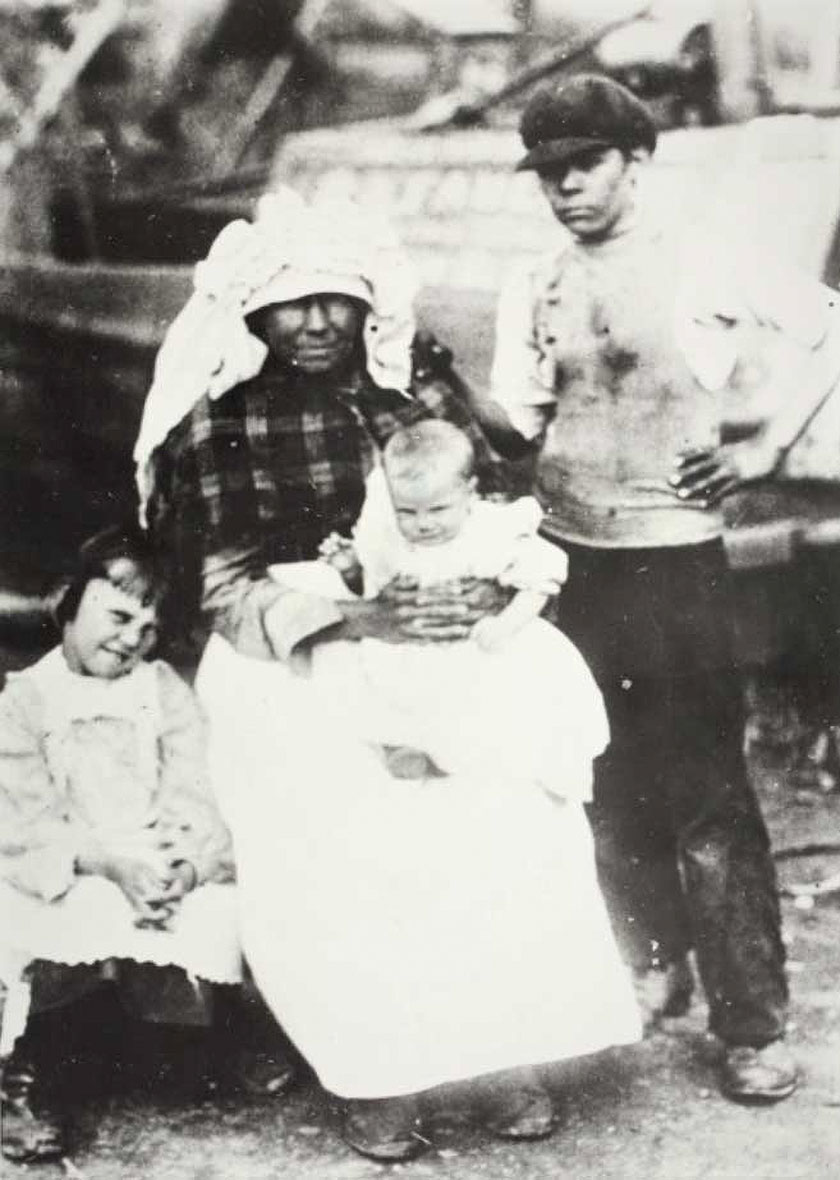

Like the men, boatwomen developed a particular style of dress. They wore layers of clothes to keep them warm, with long flannel skirts, layered with petticoats. They wore tough linen aprons over these to protect them from the dirt. Large lace bonnets were also typical for women and girls.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries many children went to work instead of to school. On narrow boats, children would start working as young as eight or nine. They were usually responsible for looking after the horse, walking with it for many miles, often more than twelve hours a day.

Education was rare for children who lived on narrow boats, because they moved around so often and over large distances. Canal companies and charities tried to help by setting up temporary school rooms in institutes, like this one at Froncysyllte but levels of literacy remained very low amongst boat children.

Living around water and busy industrial sites meant that life onboard a narrow boat was especially dangerous for children. Younger children playing and older children working were both at risk of drowning. Sadly, this means that much of what we know about their lives comes from reports of their deaths.

The style of canal boat decoration called ‘Roses and Castles’ is often considered as traditional to all narrow boats. In fact, it was rarely seen outside of the English Midlands, and almost never on the Llangollen Canal. Today it is a popular style found on many boats and canal souvenirs.

Boatwomen living on canals would spend their spare time doing crochet, a form of wool working using a small hook. They would make colourful squares and stich them together to make blankets and clothing. They would also make covers to keep the flies off the ears of canal horses.

Fenders are hung from the front and rear of narrow boats to protect them from bumping. Boatmen turned them into a decorative art as well. Complex knotted ropework and even the tails of dead horses would also decorate the ‘ram’s head’ or rudder post, at the back of the boat.

In the late nineteenth century, as many as 8,000 people were living on working narrow boats in Britain. Today, Canal and River Trust estimate that more than 15,000 people live permanently on the canals and waterways. Although the boats are rarely used for delivering cargoes, many occupants ‘work from home’ on their boats.