Objects & Artefacts

Discover more about Pontcysyllte Aqueduct and Canal through objects – the materials used to build it and the goods transported along it. The objects range from the massive limekilns at Froncysyllte to the small bolts that hold the Pontcysyllte Aqueduct together, from paintings in galleries to canal side art. Meet some of the characters behind the objects, the people who made them or used them and get an insight into life on and around the canal.

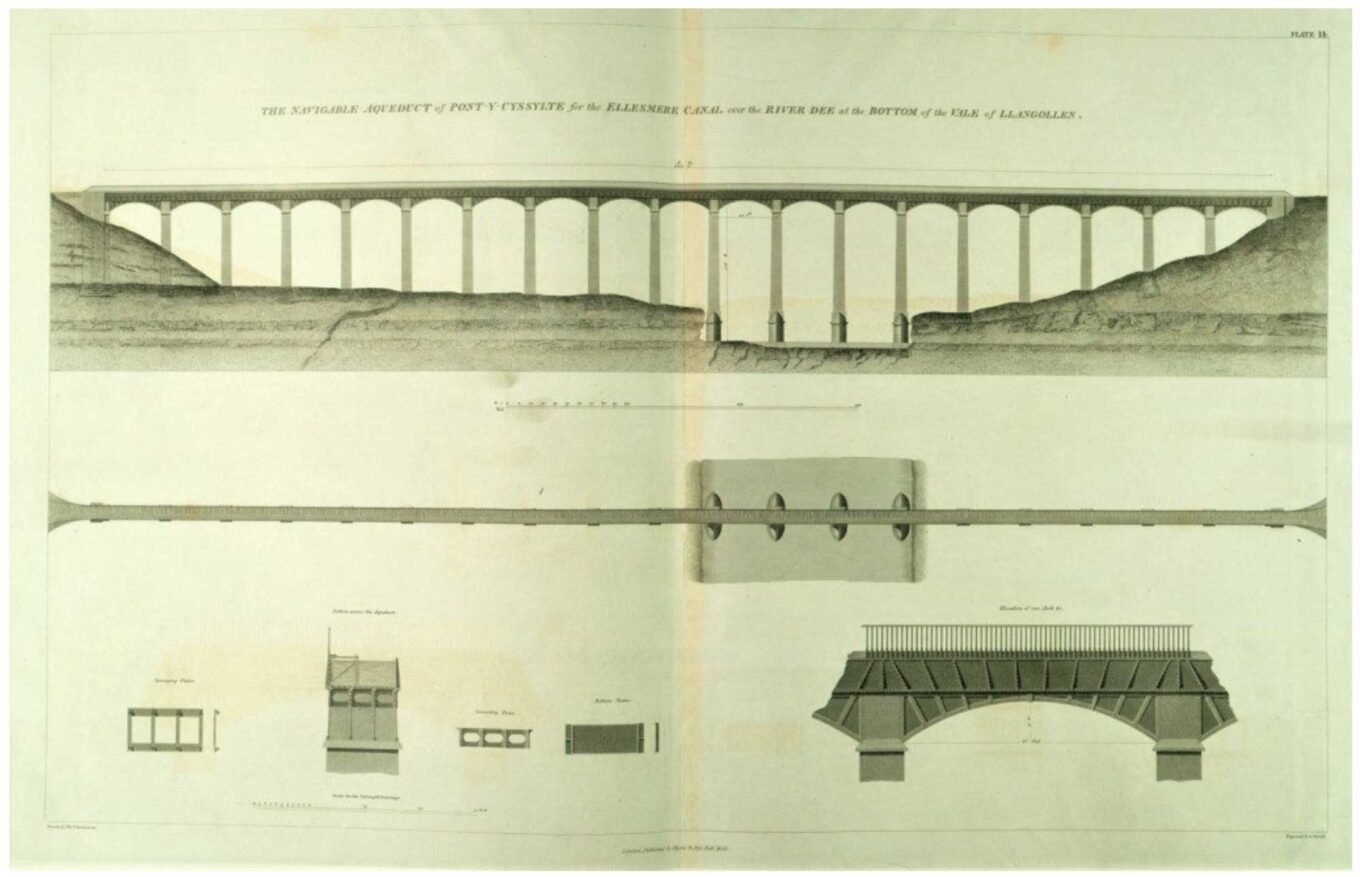

Local stone supporting the stream in the sky. The tallest sandstone piers supporting the iron trough of Pontcysyllte aqueduct over the river Dee are over 38 metres (126 feet) high.

One of around 500 wrought iron nuts and bolts that were replaced during a refurbishment of the aqueduct in 2003-4. The modern replacements were made of recycled iron.

Telford used cast iron that had been made near the canal for the aqueducts at Chirk and Pontcysyllte, in bridges over the canal, like Rhos-y-Coed bridge at Trevor, and in structures throughout Britain.

Artworks to explore along the canal. A large hand can be seen at the head of the aqueduct towpath, standing two metres tall. It is carved from limestone by Anthony Lysycia. The hand represents the many labourers who worked to build the aqueduct, and the rest of the canal, without modern machinery to help them.

Historic templates to keep the canal in working order. This pattern tells us about a disappeared part of the canal’s history. It is the only surviving evidence of a crane which operated on the Plas Kynaston branch canal. The Oil Works were part of the Graesser chemical works but in 1896 the crane was owned and maintained by the Shropshire Union Canal Company.

Connecting the quarries to the world. Tramroad wagon from Moel Faen quarry.

The canal supplies the building blocks of Victorian Britain. The clay found in the Ruabon district, north and east of the canal at Trevor, is called Etruria Marl. Like ironstone and sandstone found in this area, it has a high iron content. When it is fired it turns a rich red colour, familiar from many buildings in the villages near the canal.

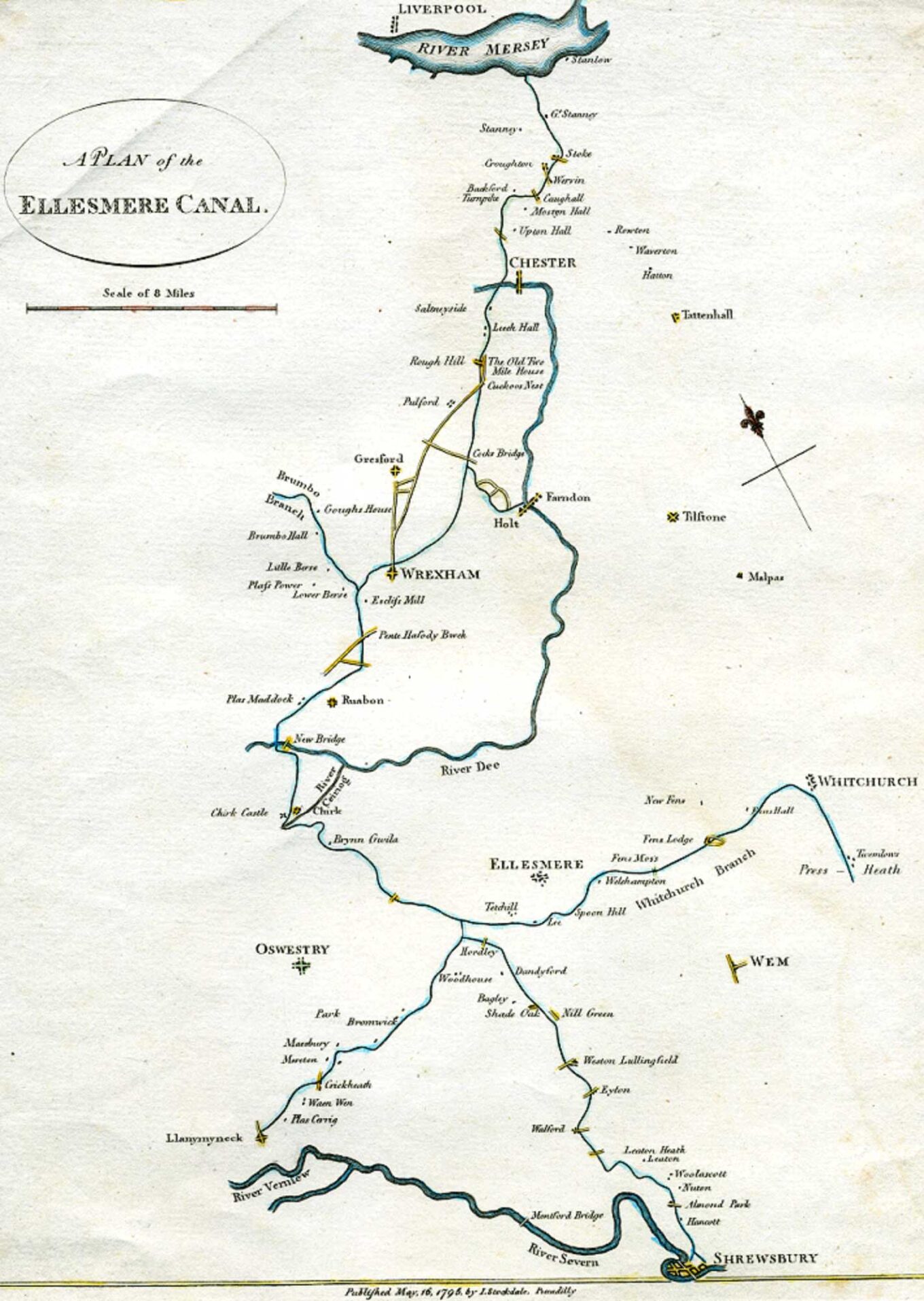

Keeping traffic flowing on and over the canal. Bridges on the Llangollen Canal are numbered in two directions, starting from Frankton Junction in Shropshire. The ‘E’ numbers count eastwards and ‘W’ numbers go westwards. Gledrid Bridge marks the start of the World Heritage Site and is number 19W. The last is King’s Bridge Viaduct at Llantysilio, number 49WA.

Capturing the beauty of the canal on canvas. This 1826 oil painting by George Arnald shows Pontcysyllte Aqueduct as it is most often depicted. It looks east, across the old Pont Cysylltau bridge over the River Dee. The landscape beyond the aqueduct is muted, to emphasise the structure, which is lit up by the low evening sun.

The simple key to life on the canal. The windlass is a simple but essential tool for boat owners and maintenance staff on the canal. It is an L-shaped metal bar, with a socket at one end. The socket fits onto a spindle of a sluice or lock gate. The windlass can then wind it open or closed.

Keeping traffic flowing on and over the canal. Bridges on the Llangollen Canal are numbered in two directions, starting from Frankton Junction in Shropshire. The ‘E’ numbers count eastwards and ‘W’ numbers go westwards. Gledrid Bridge marks the start of the World Heritage Site and is number 19W. The last is King’s Bridge Viaduct at Llantysilio, number 49WA.

The canal supplies the building blocks of Victorian Britain. The clay found in the Ruabon district, north and east of the canal at Trevor, is called Etruria Marl. Like ironstone and sandstone found in this area, it has a high iron content. When it is fired it turns a rich red colour, familiar from many buildings in the villages near the canal.

Capturing the beauty of the canal on canvas. This 1826 oil painting by George Arnald shows Pontcysyllte Aqueduct as it is most often depicted. It looks east, across the old Pont Cysylltau bridge over the River Dee. The landscape beyond the aqueduct is muted, to emphasise the structure, which is lit up by the low evening sun.

Telford used cast iron that had been made near the canal for the aqueducts at Chirk and Pontcysyllte, in bridges over the canal, like Rhos-y-Coed bridge at Trevor, and in structures throughout Britain.

Artworks to explore along the canal. A large hand can be seen at the head of the aqueduct towpath, standing two metres tall. It is carved from limestone by Anthony Lysycia. The hand represents the many labourers who worked to build the aqueduct, and the rest of the canal, without modern machinery to help them.

One of around 500 wrought iron nuts and bolts that were replaced during a refurbishment of the aqueduct in 2003-4. The modern replacements were made of recycled iron.

Historic templates to keep the canal in working order. This pattern tells us about a disappeared part of the canal’s history. It is the only surviving evidence of a crane which operated on the Plas Kynaston branch canal. The Oil Works were part of the Graesser chemical works but in 1896 the crane was owned and maintained by the Shropshire Union Canal Company.

Local stone supporting the stream in the sky. The tallest sandstone piers supporting the iron trough of Pontcysyllte aqueduct over the river Dee are over 38 metres (126 feet) high.

Connecting the quarries to the world. Tramroad wagon from Moel Faen quarry.

The simple key to life on the canal. The windlass is a simple but essential tool for boat owners and maintenance staff on the canal. It is an L-shaped metal bar, with a socket at one end. The socket fits onto a spindle of a sluice or lock gate. The windlass can then wind it open or closed.