Introduction

Chirk lies on the border between Wales and England and has two castles. The earliest is a motte and bailey castle built in the 1100s, probably to guard the crossing of the River Ceiriog. Chirk Castle was built in 1295 for King Edward I, strategically located at the entrance to Ceiriog Valley as part of his campaign to control Wales.

The canal was a huge benefit to the industries in Ceiriog Valley when it reached Chirk in 1801. Slate, silica, coal and limestone were all quarried or mined in the Valley and the canal and later the railway provided access to wider markets.

Click on any Point of Interest marker to view the description

1. Chirk Aqueduct

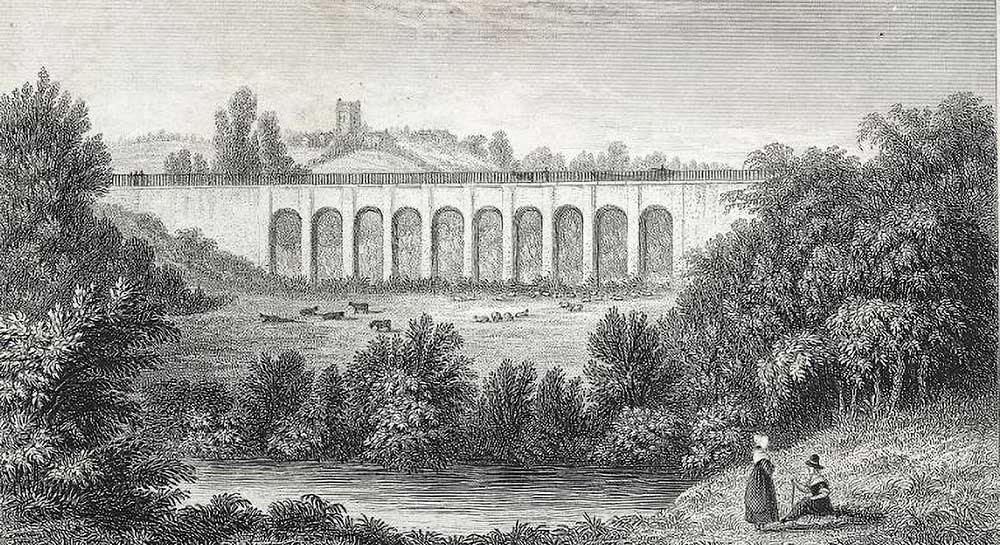

Chirk Aqueduct was the tallest navigable aqueduct in the world when it opened in 1801. Initial plans were to build a long embankment with a small aqueduct over the River Ceiriog but Richard Myddelton of Chirk Castle objected as it would have spoilt his view.

So William Jessop and Thomas Telford proposed an aqueduct that ‘instead of an obstruction, it would be a romantic feature in the view’, avoiding damage to the river meadows and very expensive steep embankments.

© Jo Danson

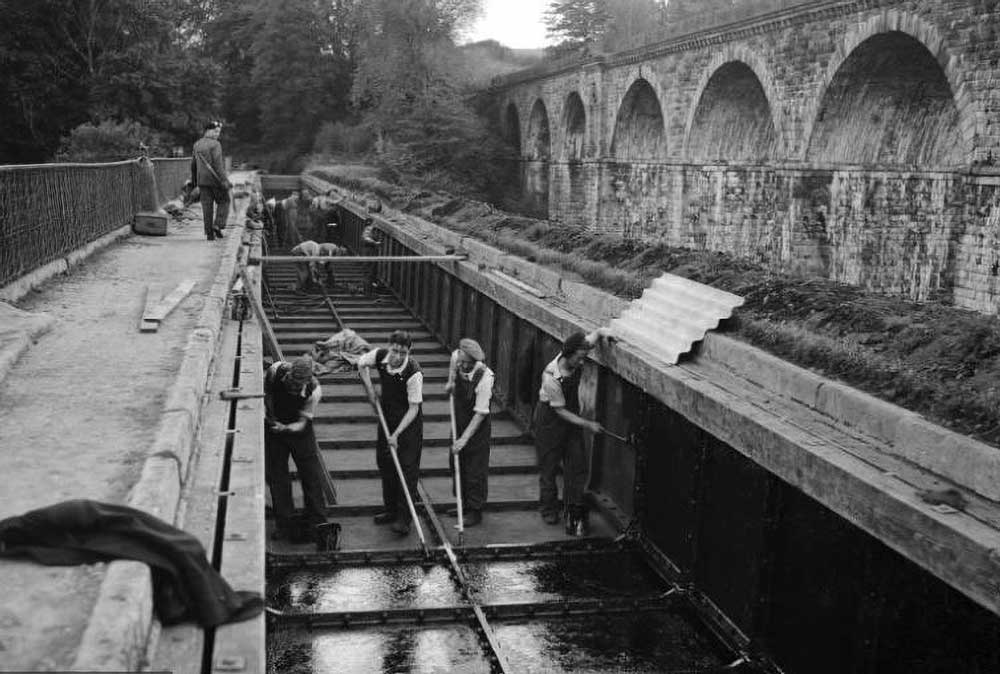

New techniques were needed to build an aqueduct 220 metres/710 feet long and 21 metres/70 feet above the river. Ten hollow stone arches carry iron plates to form the bed of the canal. The sides of the trough were originally made waterproof with high-fired brick and mortar and faced with stone but iron side plates were installed in 1869.

Painters came here to capture what was considered to be a romantic feature. In 1799 before the aqueduct was completed, the artist Richard Colt Hoare painted the scene and wrote that he ‘stopped to take a view of the noble aqueduct that is forming across the valley’. The painting also shows the engineers’ house, Telford Lodge, now known as Min y waen, in the distance. Samuel Lacey captured the scene looking towards Chirk in 1820 and Henry Gastineau painted the scene from another angle in 1834 showing the elegant aqueduct crossing the River Ceiriog, a few years before the railway viaduct was built.

The aqueduct marks the boundary between England and Wales which follows the old river course, seen as a low depression.

© Crown copyright: RCAHMW

© Jo Danson

Chirk Aqueduct by Samuel Lacey, 1820 © By permission of The National Library of Wales

Workmen clearing Chirk Aqueduct 1954 © By permission of The National Library of Wales

2. Chirk Viaduct

Towering over the aqueduct is Chirk Viaduct, carrying the Ruabon to Chester railway over the River Ceiriog. Completed in 1848, it was this railway that would eventually play a part in the demise of the canal as a transport route for goods.

© Jo Danson

Listen to…

…the sound of a train crossing the viaduct

Henry Robertson, the railway engineer, had successfully campaigned to get approval for a railway line that would link Ruabon to Chester via Wrexham in 1845. He was keen to extend this line to Shrewsbury as he recognised the need to transport goods further afield. His proposal was complex as the line had to cross both the Dee and Ceiriog rivers as well as overcome opposition from local landowners. He was successful and appointed Thomas Brassey as the general contractor.

The viaduct over the River Ceiriog was smaller than the one over the River Dee but still 260 metres/849 feet long and 30 metres/100 feet in high. It took two years to build and originally had ten stone arches with three wooden arches on either side but these were replaced by six stone spans after 10 years.

The line became part of the Great Western Railway system in 1854.

© Crown copyright: RCAHMW

© Jo Danson

3. Chirk Tunnel

Chirk Tunnel was one of the first British canal tunnels to be built with a towpath.

The tunnel is the longest on the canal at 421 metres or 460 yards and took seven years to build. The stone tunnel entrance is slightly flared making it easier for boats to enter while the fact it is straight means it is easier to see boats coming in the opposite direction.

© Jo Danson

The canal could have been dug in a cutting, but Richard Myddelton of Chirk Castle refused to allow the canal to break his access to the town of Chirk, even though he was a keen supporter of the project.

‘Cut and cover’ was the preferred method of construction. The ground was opened in different lengths so the brickwork could be made perfect, and then the arch was secured with loose stones and excavated spoil. The brickwork was sealed with clay to keep the tunnel dry.

In 1822 the cantilevered towpath was reconstructed, supported by brick arches which allows the water to flow underneath to reduce the drag on the boats. It also incorporated an iron handrail, the railing curving into the ground so it did not snag the towrope.

Just in front of the tunnel is a diamond-shaped canal basin, where boats can wait if necessary, to enter the tunnel. The basin was the end of the canal from Frankton Locks to Chirk Aqueduct when it was opened in 1801.

Wharfage facilities were provided here, with a pulley arrangement to help haul goods up to the road above the canal. A weighbridge and canal worker’s hut were situated by the basin in the 1800s.

© Crown copyright: RCAHMW

4. Chirk Railway Station

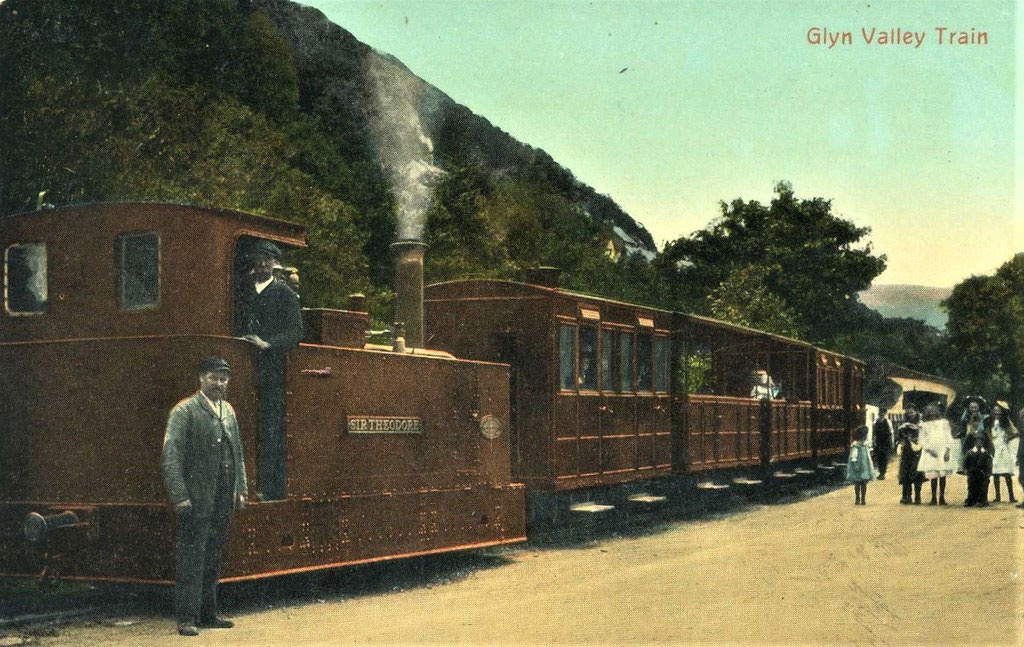

Chirk railway station was a fine sandstone building built in 1848 when the new Chester to Shrewsbury line opened. It was also the terminus for the Glyn Valley Tramway which brought slate, stone, flannel and gunpowder from the Ceiriog Valley. At one time Cadbury’s factory had their own siding to take the cocoa liquor to the chocolate factory at Bournville.

© Jo Danson

Hostility from landowners to the new railway line had meant that Henry Robertson, the engineer, had to survey some of the proposed line by night. One irate landowner wished that someone would ‘throw Robertson and his theodolite, used for surveying, into the canal!’

Glyn Valley Tramway was connected to Chirk Station in 1888. Most of the trains were mixed, carrying goods and passengers although there were special passenger excursions during the summer and at bank holidays. The tramway closed in 1935 but you can still see the spare arch in the road bridge at Chirk Station.

Queen Victoria passed through Chirk by train on her visit to North Wales in 1889. Elaborate plans were drawn up to welcome her and a guard of forty senior railway staff gathered together to shout ‘God save the Queen’. Sadly the Queen had the blinds firmly drawn in her carriage!

The station closed for goods in 1964 but there is still a private siding to deliver timber to the Kronospan factory that produces chipboard and other wood-based panels.

The original stone station was demolished in 1987.

Glyn Valley Tramway

Station Road © Graham Greasley

5. Chirk Castle

Chirk Castle was the home of the Myddelton family for over 400 years. Sir Thomas Myddelton bought Chirk Castle in 1595 and turned the medieval fortress into an elegant family home.

© Crown copyright: RCAHMW

Chirk Castle was built in 1295 as part of King Edward I’s campaign to control Wales, strategically located at the entrance to Ceiriog Valley. The only medieval part of the castle left is the main entrance frontage that contains Adam’s Tower where you can see the guardroom with the dungeon beneath it.

Sir Thomas Myddelton I was a successful businessman and was one of the first investors in the East India Company who traded in cotton, silk, sugar, spices, tea and other supplies.

The castle was extensively restored by Sir Thomas Myddelton II in the mid-1600s after significant damage in the English Civil War.

From 1911 the castle was leased to Thomas Scott-Ellis, 8th Lord Howard of Walden, a soldier and artist, poet and playwright, Olympic sportsman, medievalist and pioneer. Amongst the famous guests who signed the visitors’ book were King George V and Queen Mary, the writers Rudyard Kipling and George Bernard Shaw and the artist Augustus John who found his host sitting in an armchair dressed in full armour!

The National Trust purchased the castle in 1978 and the Myddelton family continued to live in a private apartment until 2004 when they moved to a house on the castle estate.

From the collections of the National Monuments Record of Wales: © Central Office of Information Photographic Collection

© Jo Danson

© Jo Danson

6. Hand Hotel

The original hotel building was the town house of Chirk Castle estate, established to provide entertainment such as archery for the local gentry. By the 1780s it was an important coaching inn serving travellers when various toll roads were developed in the area.

© Graham Greasley

The hotel is named after the red or bloody hand of the crest of the Myddelton family and there are various legends about the origins of this. One is that Lord Myddelton was unsure which of his twin sons was born first. When he was dying he challenged his sons to race on horseback around the castle. He said that the first son to return and touch his deathbed would inherit the estate. The story goes that the race was a close one. As the sons tore upstairs one of the sons tripped up. Realising he would lose the race he sliced off his hand and threw it on to his father’s bed claiming his right to inherit the estate.

The hotel was extended to cater for the increase in trade brought by the improved London to Holyhead road. Ellis Davies was a coachman and an ostler, who looked after the horses, at the Hand Hotel in the 1870s. One day he was thrown from the carriage when the horses took fright on a journey and lay unconscious on the road until ‘stimulants’ were brought. He was fortunate not to have his inquest here, unlike the many colliers whose inquests were held at the Hand.

© Jo Danson

© Graham Greasley

7. Hand Terrace and National Schools of Charlotte Myddelton- Biddulph

When Charlotte Myddelton-Biddulph inherited the Castle in 1819 she also inherited virtually the whole of Chirk. She stated that her ambition was to improve both the appearance and amenities in Chirk and she soon set about improving the area which benefited the town enormously.

Hand Terrace was built in the 1820s, a row of seven properties similar to almshouses with window openings bricked up to avoid the window tax.

Charlotte was also responsible for building Chirk Boys’ School and Chirk Girls’ School which provided education for the poorer families in accordance with the teaching of the Anglican Church.

The Boys’ School, next to the Hand Hotel, could originally accommodate 100 boys but was extended in 1857 to accommodate 123 pupils. Small payments were made by some parents towards the schoolmaster’s salary. It later became the headquarters of the Royal British Legion and was given to them in 1964 by the Myddelton family.

The Girls’ School, built in 1843, was designed by Augustus Pugin in a Gothic style and cost £450. It was extended in 1874 and again in 1905 when it was used for adult education classes including evening classes in mining. The school became a furniture warehouse in 1970.

© Courtesey of Graham Greasley

The Girls’ School © Jo Danson

Hand Terrace © Graham Greasley

Parish Hall & Girls School © Graham Greasley

8. War Memorial

The War Memorial and the Recreation Ground were the gifts of Lord Howard de Walden. He was a soldier in the 10th Royal Hussars in the Boer War in South Africa and resumed active service in World War I serving with the 9th Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers in Gallipoli and France.

The War Memorial was created by the famous designer and sculptor Eric Gill, best known for his typeface Gill Sans. It was made from Portland Stone and unveiled on 17 October 1920. The sculpture on one side of it has a soldier bent over his rifle and bayonet, wearing a long coat and helmet.

Two sides of the memorial commemorate the 66 men from Chirk and the surrounding area killed in World War I while the names of 19 men killed in World War II were added later.

The wars touched the lives of men from all walks of life from landed gentry to coal miners and railwaymen.

© Jo Danson

9. St Mary’s Church

St Mary’s dates back to 1130 when it was built next to the ‘motte and bailey’ castle. The church was originally dedicated to St Tysilio but was probably changed to St Mary’s in the 1200s when the monks of Valle Crucis Abbey took over the church.

© Jo Danson

The church was extended with an additional nave in 1519. Although it was altered and repaired several times it retains much of its medieval character with fine carved roofs. There are also some outstanding monuments, including some to the Myddeltons. In the past rivalry between the Myddelton family of Chirk Castle and the Trevor family of nearby Brynkinalt Hall led to a dispute and a court case about where the two families could sit in the church in the 1620s!

A curfew bell was rung in the evening from Norman times until the 1800s. The bell was probably housed in an external free-standing bell before the tower was built in 1475. Records show that there were three bells in the tower in 1650 but by 1814 there were six bells which were recast and refitted that year.

The ringers were sometimes paid with ale, as was recorded in the 1688 churchwarden’s accounts, and payments of this kind lasted until about 1820. Ringing the ’broth bell’ at the end of the service told those left at home to get ready to serve the dinner! Enthusiastic bell ringers still carry on the tradition of summoning the faithful to church and to mark local and national celebrations.

© Jo Danson

John Varley painting, 1820: From the collections of the National Monuments Record of Wales: © Ceredigion County Council

10. Chirk Bridge and Holyhead Road

The London Holyhead road was one of the major feats of engineering of the era and included major embankments, cuttings, causeways and bridges including the Waterloo Bridge at Betws y Coed and the magnificent Menai Suspension Bridge.

© Jo Danson

Severe flooding in 1706 altered the course of the River Ceiriog and swept several bridges away including the one at Chirk. A new bridge was built and repaired several times before a new high arched stone bridge designed by Thomas Telford was built by John Simpson in 1793.

Following the Act of Union between Britain and Ireland that came into effect in 1801, a faster and more reliable route was needed between London and Dublin for the mail coaches and the Irish MPs who now needed to be present in Parliament in London.

In 1811 Thomas Telford was appointed to survey the 83 mile route from Chirk to Holyhead, the first major civil engineering project directly funded by Parliament. Work on the whole route started in 1815 and was completed in 1826. Telford was able to use the experience he had gained on the canal, particularly in design and contract management.

The climb from the river up to town presented a challenge and despite the massive embankment this is the steepest section of the road with a gradient of 1 in 20. This was a big improvement on the turnpike road but steeper than the recommended gradient of 1 in 30, the steepest at which galloping horses could pull a stage-coach.

Large retaining walls were constructed to help prevent landslides affecting the road and milestones with iron plates were placed all along the route, so that travellers could see how they were progressing on their journey. Toll houses were built in a distinctive shape which gave the toll keeper a good view of the road from all directions. The houses included living accommodation for the toll keeper and his family.

Little more than 20 years later after these road improvements the spreading network of railways lead to the demise of the horse drawn carriages.

© Jo Danson